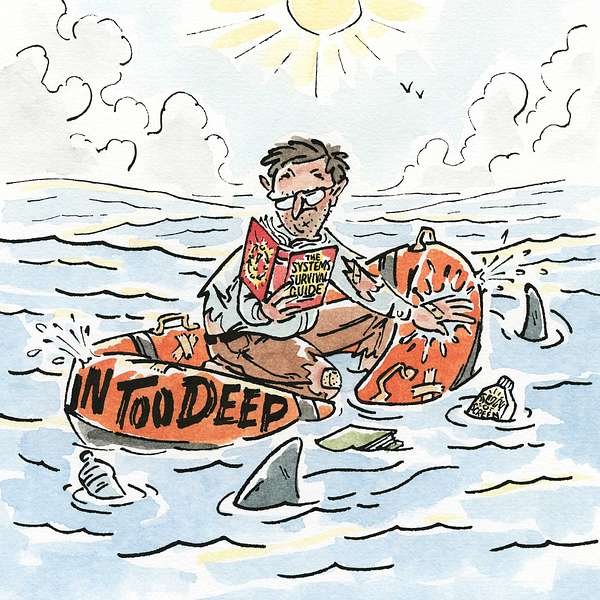

In Too Deep

We explore how changemakers across the globe are engaging complexity to tackle tough issues. Created by the team at Kumu.io

In Too Deep

The systems behind the symptoms | Episode 15

What if the real problem isn’t what we think it is? When simple solutions don’t actually move the needle, it’s often a sign we’re treating symptoms, not systems. In this episode, Jeff Mohr talks with Matt Healey, founder of First Person Consulting, about how systems thinking and evaluation can help us move beyond surface-level problems.

They explore:

- The difference between program evaluation and systems evaluation

- Moving from problems to possibilities

- Monitoring system health and finding leverage points

- How to apply the System Effects approach in projects

- Bridging the gap between insights and meaningful action

Whether you’re designing programs, mapping systems, evaluating impact, or trying to create lasting change, this conversation is packed with insights you can use!

Subscribe to the In Too Deep Podcast or read the full transcript on the In Too Deep blog.

Mentioned in this episode:

- First Person Consulting

- Problems to Possibilities Canvas

- System Effects

- Resources on Lawyer Wellbeing: System Effects Report, Journal Paper & Theory of Change Model

J: Thank you, Matt, for joining us today. I’d love to start by having you share a bit about your background; what brought you to the work you’re doing now? And if you can, weave in any stories about when or how you started moving toward more of a systems or complexity-aware perspective.

M: Thanks, Jeff, for having me. I mean, the journey into the systems space probably wasn’t radical by any means. My academic background started out more in what I’ll call the harder sciences, archaeology was actually where I began. But after a brief stint overseas in the US on exchange, I found myself a bit dissatisfied with the idea that you could hold a view or a theory for a long time, think of it as correct, and then have it disproven, maybe even while you’re on your deathbed, by someone else. I guess I was unsettled by that sense of inherent unknowingness — which is kind of funny when we start talking about systems later — and the lack of certainty around it.

At the same time, I was really drawn to anthropology, which is closely related. So I pivoted into that field. What I liked about the anthropological view of people, culture, and society is that even though things change and any understanding is really only correct for a moment in time, you can still develop a meaningful sense of what’s happening in that moment, even if it eventually evolves or shifts.

After that, I ended up in the typical graduate situation of wondering, what on earth am I going to do for work? So I went on to do postgraduate study in environmental science. Coming from country Victoria, here in Australia, I’ve always had a bit of an affinity for the environment. I also found myself really interested in the social side of environmental issues.

There is obviously a lot of work focused on biology and ecology, but I was drawn to the human dimensions of those problems. A lot of environmental issues are actually human problems, especially when it comes to decision making and the way we manage things.

So I went through that process, thought, yes, this is that middle space I’m interested in. Now I just need a job. And I probably put off making that decision longer than I should have.

It was almost by chance that I came across an entry-level role at a small consulting firm in Melbourne that worked in program evaluation. I hadn’t heard of evaluation before, had no idea what it was, but I got the job. And that ended up being my first real foray into evaluation.

It was actually through a specific project that we began to explore social network analysis. We applied this technique to address some of the questions we were dealing with in the scope of the evaluation. I had never encountered it before in any way, shape, or form. It was one of those moments of introduction that, while brief, seemed to blend a lot of things I had always been unknowingly interested in.

That was probably the key tipping point for me, the moment when I realized “This is amazing”. It resonated so strongly with me, and it marked the beginning of my deeper involvement with it. From that point onward, my interest in social network analysis only grew, and I started actively seeking out opportunities to apply it more.

And to be honest, since we’re talking about systems, we didn’t use KUMU in the early stages of that project. I’m not even sure if you all were around at that time.

J: We’ve been around since 2011, but we were only available to anyone actively trying to find us back then.

M: Yeah, so, we used a different platform for that project, and I think that experience influenced my own approach to systems practice. Specifically, it helped me recognize the importance of ease of use and the ability to engage with platforms. While the technical aspects are essential, they aren’t always as important as making the platform accessible and engaging for people. For someone like me, who understands the technical side, it’s easier, but for those who are new to it or are presented with visuals and similar tools, there’s a degree of design and intentionality that comes into play. That’s something you don’t always get with other platforms.

It was actually after that project that we were introduced to Kumu. As you’ve advanced your offerings in that space, it’s really supported us in our work as well. I think some of the things in your approach resonate deeply with how we develop things in our own practice.

J: Can you tell me a bit about the origin story of First Person Consulting, including any background on the name? Also, if you’d like, feel free to dive a bit deeper into the three primary areas of work you focus on, and how separate or interconnected they tend to be in the projects you work on.

M: Yeah, for sure. So, I mentioned that I started in evaluation at this small consulting firm. It was during this time that I had the fortunate opportunity to meet two other members, Dan Healy and Patrick Gilmour.

Like I mentioned before, my personal experience comes from rural Victoria, and academically, I was focused on anthropology and the social dimensions of the environment. Dan, on the other hand, has a PhD in social psychology. He applied his research to studying networks, particularly how farmers manage land holdings through information and resource sharing — very quantitative work with a strong network element. And then Patrick’s background was in marine ecology. We eventually decided to form First Person Consulting, or FPC.

We came up with the name in a way that might not be as common today, since people now often use AI platforms to support brainstorming. But back then, it was classic gathering around a whiteboard, throwing out ideas, and leaning into the types of work we wanted to do. We didn’t want to be too narrowly defined by just evaluation.

By that point, I had become quite aware, even in my two years at the company, that while evaluation is a significant field, there are other areas that overlap with it. There’s a gray area, a bit of a fuzziness, between what’s strictly evaluation and what falls into other domains. So, we had to consider a few classic marketing questions — what’s the first thing people will see? How do we want to present ourselves? And, of course, who’s our target audience?

We definitely didn’t want to use a made-up name. We did a lot of phone interviews, and if you called a farmer on his tractor in the middle of a paddock and introduced yourself with a name that wasn’t even a real word, the usual responses were either confusion or just hanging up. So, we needed something simple and straightforward. “Consulting” had to be in the title so people would immediately understand that we were consultants.

The “First Person” part of the name was chosen to reflect how we approach our work. In the early stages, we decided that while evaluation was one of our core services, we also focused on research and, at the time, strategic planning (we used “planning” instead of “design”). It felt right, especially when we thought about the inclusive nature of first-person language. It aligned with our collaborative and flexible approach to work. Over the years, some clients have even asked if the name suggests that we’re the first people you call when you need help. But for us, the name always centered on the areas of work we wanted to emphasize — the “seed” from which everything grew.

As you may have noticed, I didn’t initially mention anything related to systems-based work. That’s actually a more recent addition, probably within the last four years. Leading into the pandemic, we started seeing a growing interest in things like social network analysis and various forms of systems mapping. This led us to rethink our areas of focus.

Previously, we had separate buckets for human-centered design, strategic design, evaluation, and research. But as interest in systems grew, particularly alongside these other areas, we realized that fields like systems design and evaluating systems change were becoming more relevant. There was a lot of overlap between these areas, especially in place-based approaches and similar topics.

So, we reorganized a bit to better reflect how we were working. A lot of the design work and social research naturally fit together, so that now sits under one umbrella. Evaluation still makes up about 80% of our work across the team. Then, we introduced what we now call “systems practice” as our third main stream, which has been a major focus in recent years.

The shift toward systems thinking came from the growing interest in these interconnected issues. For instance, when considering strategic direction or designing a program, what role does systems thinking play? How do we contextualize these challenges within complex systems? Similarly, if we evaluate a program that hasn’t worked, how do we consider external influences or factors that might have affected its outcome? And with systems change efforts, how do we evaluate those? How is that different from evaluating a program?

There has been a significant uptick in interest in this space. It’s not unique to Australia, but it’s definitely becoming more common here. Systems thinking, complexity, and related fields are gaining more attention, and this is something we’ve grown into, particularly as my own interest has deepened. As consultants, we always follow where the work leads us — work that resonates with us. We’ve been fortunate that much of the work in this space is focused on public-purpose or for-purpose causes, like social justice, public health, and environmental challenges.

J: Yeah, I’d love to stay with the evaluation lens for a moment and circle back to your point about the difference between evaluating a program and evaluating systems change. I’m also curious about how that compares to more traditional forms of evaluation, especially for people who are used to those approaches, versus a more systems-focused or complexity-aware perspective.

Could you talk us through that? Both in terms of your own journey — how your approach to evaluation has evolved — and some of the things you’re now doing in your evaluation practice, particularly when it comes to evaluating systems change. What approaches or methods have you found work really well in that space?

I also know you’ve done work around monitoring systems health, too. If it makes sense, feel free to bring that in — especially any practices or language you’re using that seem to be resonating with the people you’re working with right now.

M: Yeah, absolutely. Like I mentioned before, I hadn’t really come across evaluation until I started in that particular role at that firm. And honestly, my introduction to evaluation was pretty standard.

A lot of evaluation processes, especially in the beginning, tend to follow a typical approach. You usually start with some fairly broad definitions of what it means to evaluate something. Even at that stage, people begin to realize there are different interpretations of what that actually means.

But generally, most of those definitions revolve around this idea of value. You’ll hear people talk about the merit, worth, or value of a thing — as if you can evaluate pretty much anything, right? But it always comes back to: What’s the merit? What’s the worth? What’s the value of this thing you’re looking at?

And I think one realization that’s really stuck with me — and this is something I’ve probably only been able to articulate clearly in the last year or so, though maybe I understood it implicitly before — is how that framing positions you as separate from whatever it is you’re evaluating. It’s like: Here’s this thing over there, and you’re over here, judging it from a distance.

That’s been a really important shift in my thinking, recognizing that how you position yourself, as the evaluator, in relation to what you’re evaluating… that actually matters a lot.

There are definitely practices, fields, or approaches within evaluation that are quite explicit about where you, as the evaluator, are positioned. But that traditional introduction to evaluation tends to follow a pretty standard model. It’s usually framed around this idea that there’s a thing — a program, a project, an initiative — and you are going to evaluate it.

And typically, the way you do that starts with developing a logic model, or some kind of diagrammatic representation of what’s supposed to happen. You might say, “Okay, we’re going to run workshops”, “we’re going to engage people”, “we’re going to provide information”, with the hope that those activities will change behavior. From there, you map it out in this fairly linear way: In the short term, people gain knowledge, maybe they learn how to be healthier. Then, because they have that information, they feel more confident putting it into action. And if they do that, and everything goes as planned, they’ll actually be healthier.

And ultimately, the big-picture benefit is better population health outcomes. Now, obviously, I’m glossing over a lot of details, but that’s the typical, traditional approach to evaluation.

That’s also how I started in my practice. Even when I was working on other types of projects, like social network analysis — or SNA — I still thought of them as separate pieces. Like, SNA is just another method, another tool in the evaluator’s toolkit. You still do surveys, you still do interviews, and SNA was just an add-on to that process.

But when you start thinking about evaluating systems, it becomes something different. You’re no longer just tracking activities and outcomes in a straight line. Instead, you’re trying to understand the broader context, the range of factors at play within a system. It’s not about ignoring those traditional pieces, but about stepping back and asking “How do all these things interact within the bigger picture?”, “What are the dynamics at play?”

This is where you get into that stereotypical systems language — everything’s interconnected, everything’s always changing — and yes, from an evaluation perspective, that’s part of it.

But I actually think this is where people sometimes overcomplicate things when they talk about evaluating systems. Because really, at its core, all you’re doing is shifting the focus of your questions.

In a typical program evaluation, you might ask:

- How many people attended the workshops?

- How many people feel more confident?

- How many people have changed their behavior?

With systems evaluation, you’re asking similar types of questions, but instead of asking them about a single program or intervention, you’re asking them about the system itself, about the dynamics within that system.

So instead of starting with a linear logic model that outlines what the program does, you’re trying to build something more like a systems map, or a dynamic model, that reflects how the system operates.

Of course, you have to acknowledge the limitations of trying to “snapshot” a system. But the goal is to capture those dynamics as accurately as you can, and then start asking questions of that system. Within that system will be the program you’re evaluating, sure, but there’ll also be other programs, other actors, even vested interests — say, organizations pushing unhealthy products — all of which influence what’s happening.

Now, traditional evaluation sometimes factors these in. They’ll call them assumptions or external factors. But usually, the main focus still stays on that one program.

What you’re doing with a systems evaluation approach is recognizing that the program is just one piece among many. So yes, you may still ask questions about it — but ultimately, your focus shifts to asking questions about the system as a whole. That’s what you’re really trying to evaluate.

The thing that’s really followed on for me from all of this is… okay, what does that actually mean in practice? What kinds of questions are you asking that are actually different from the usual ones?

And, to be honest, in some ways, the questions themselves aren’t that different — it’s really just a different level of thinking.

So, you might still be asking “How many people are involved?” But now, you’re also asking “Who are those people?”, “ Which populations or communities are being included in these programs?”, “Who’s being excluded?”, “Who’s not being reached?”

You start asking questions like:

- Who holds power here?

- Who’s making the decisions?

- Where is the money going, and where isn’t it going?

In some ways, they’re still familiar questions, but now you’re asking them of a much broader, more complex system. I think the real challenge isn’t just understanding the system itself. The harder part is figuring out how to evaluate change within that system.

If you go back to the idea of evaluating merit, worth, or value, you quickly realize you have to land on some kind of process, some way of deciding: Who gets to determine what’s valuable? Who decides what counts as beneficial? And that’s tough. It’s messy. I think that’s where a lot of people get stuck, because those aren’t simple or comfortable questions to answer.

And asking those kinds of questions also tends to position you, whether you realize it or not, as somehow separate from the system you’re evaluating. If I’m sitting here saying, “We’ve got this population health system, and we want to evaluate how it’s changed”, even just framing it like that, especially if I’m staring at a model or diagram on a screen, I’m already casting myself as an outsider.

But the reality is, I might actually live in that community. I might even be directly affected by those health outcomes. So I think it’s really important to hold that awareness . To be mindful of how you’re positioning yourself in relation to the system you’re trying to understand or evaluate.

Inevitably, people always come back to the question: But how do we actually do it? And I think this is where traditional training tends to push people toward looking for individual indicators, outcome measures, and other familiar tools.

You mentioned monitoring systems before, and I won’t pretend I invented that idea. It’s hardly new. But I do find it useful as an analogy to help explain this work to others. For me, it feels intuitive because I’ve been immersed in it for a while. But for people who are new, it often feels abstract. They ask: “What’s the thing we look for to know whether our system is healthy or doing the right things?”

In a lot of foundational systems training, people use analogies, especially the human body, to help make sense of complexity. And that really resonates with me. The human body itself is a system made up of subsystems: skeletal, circulatory, respiratory, and so on. When you go for a general health check, it’s not about diagnosing a specific problem, but rather getting a sense of your overall state of health.

That’s the mindset I think can be useful here. Because when it comes to evaluating systems, people often get stuck thinking they have to assess everything at once. Instead, it might be more practical to start small, something straightforward enough to build on over time.

Say we’ve conceptualized a system in a particular community — maybe we’ve even named it, like “The Physical Activity System” for a certain region. It includes sporting clubs, local government, community groups, and all the programs they run. But there are also barriers; accessibility, cost of living, social factors. With all these moving parts, how do we get a general sense of whether the system, as a whole, is healthy?

Sure, you could look at a broad population health measure. But the problem is, those data often take years to emerge. By the time you see it, it’s already outdated. That’s why I think it’s important to look for something more current. Something contemporary that holds meaning, value, and relevance for the community itself. Not something I decide on, but something developed through shared understanding. It’s a bit like taking your temperature. It’s not perfect, it doesn’t tell you everything, but it gives you a quick sense of how things are going.

And the same principle applies to subsystems. You can do targeted checks, like you would with the circulatory system, and apply that “temperature check” logic across different parts of the system.

Ultimately, these kinds of entry points into systems thinking, complexity, and evaluation are critical. And it’s not about discarding the traditional methods we’ve been trained in. It’s about being open to reshaping and adapting them, recognizing that while we can’t evaluate a system in exactly the same way we evaluate a program, we can still use familiar tools if we’re willing to adjust how we apply them.

J: When you’re talking about building that systems view, identifying subsystems, thinking about the “temperature check” idea, am I understanding you right that you’re suggesting there might be temperature checks at different levels? Like, one at the overall system level and others at the subsystem level?

And when people are trying to figure this out — when they’re wrestling with questions like “Is this actually a subsystem?”, “Or should I just treat it as part of the bigger system?” — what’s your practical advice?

How do you guide people through that decision-making? How do you help them figure out where and how to break things down into subsystems, and, from a temperature check point of view, what’s “enough” to get a meaningful sense of what’s going on?

M: Yeah, I think the place I usually start is by making a distinction between actors and factors. That’s the way I tend to approach systems mapping in general. By actors, I mean organizations, people, partnerships — the human side of the system. And by factors, I’m talking about the broader determinants of health, systemic influences, processes. Basically the conditions that shape outcomes in a given space or community.

So as an initial step, I’d typically start there. For example, when I’m working with organizations, partnerships are often the most common entry point. You might start by asking: Who are the key players in this context? Who’s working toward similar goals at the community level? And where are there differences in perspectives or priorities? One practical way to think about it is by looking at partnership health. How do you assess whether a partnership is functioning well?

To give a recent example — a project I’ve been involved with in Queensland, here in Australia — we’ve been working on something that isn’t tied to a specific program, but focuses more broadly on organizations connected to childhood wellbeing. We’ve been collaborating with the Thriving Queensland Kids Partnership, which acts as a convening or intermediary organization. Their goal is to help align a wide range of groups around the shared aim of improving wellbeing for all children in Queensland.

What they wanted to understand was pretty straightforward: Who are the organizations involved? What do they do? Who do they work with? — all in relation to childhood wellbeing. And importantly, this wasn’t tied to any one program. It was more about interest, role, and stake in the space.

For that work, we ended up boiling the idea of partnership health down to two key elements: purpose and process.

- Purpose is about alignment; shared values, shared goals, and a clear sense of why the partnership exists and what each organization’s role is within it.

- Process is about function; how well the partnership actually works in practice.

That’s the kind of starting point I tend to use when thinking about subsystems or deciding where to “draw the lines” in a system map. It helps anchor the work in something both practical and meaningful. I’ve often found it tricky to merge those two dimensions, because they don’t always align neatly.

You can have partnerships that function really well on paper: great relationships, smooth meetings, good work getting done. But then you have to ask, “Is this actually contributing to the bigger picture?”, “Are we moving toward that higher-level vision we set out to achieve?”

On the flip side, you might have partnerships where, on paper, it makes sense for the organizations to be working together, but it just doesn’t click. Maybe it’s a personal dynamic, or maybe the structures and systems don’t support effective collaboration. Either way, it’s tough to wrap both of those into a single concept of “partnership health.” That’s why I think it’s useful to look at purpose and process as distinct dimensions.

But even beyond that, I think there’s a need to see those partnership dynamics as separate from the broader determinants, the factors that actually influence outcomes for, say, children in a community. Some of those factors will be within your sphere of influence. Others will be way beyond it, things like climate anxiety, global environmental challenges, or societal pressures. You can’t control those from within a single community, but they still shape how kids in that community feel and how well they thrive.

So if we take that as our focus: “What influences whether kids are thriving here?”, the next question is, “What are the range of factors at play?” And once we’ve mapped those out, are there indicators we can use, something like a temperature check, to give us a general sense of how things are going?

For example, if climate anxiety is a concern, how would we even begin to understand whether young people in our community are generally feeling anxious about their future, or not? What could we look for that gives us meaningful insight, even if it’s not a perfect measure?

I keep saying it, but it’s very much like a temperature check, that’s the best way I can describe it. It’s a proxy for the general state of health, but it’s not a diagnostic tool. It doesn’t tell you exactly what’s wrong or what needs fixing. Instead, it’s just a starting point. It’s about asking: How are things going right now? You might know that, down the line, you need to address big issues like capitalism or climate change. But right now, where do we stand?

A year from now, things could look completely different, but the trade-off is this: You don’t want to over-invest in measuring every single part of the system. Imagine spending an entire year just conceptualizing, measuring, and analyzing all the data, only to realize that things aren’t great, without knowing what to do about it. That’s the risk.

So, to answer your question more succinctly: I think of it in terms of two dimensions. First, there’s the actor dimension — who the people, players, and groups are. Then, there’s the determinants dimension — what factors are influencing the issue.

From there, you can drill down further. For instance, you could examine different types of organizations or groups within a community, or look at specific subsystems like education or physical health. For example, if you wanted to focus on childhood wellbeing, you might break it down into the educational subsystem and the physical health subsystem.

But the most important thing is that any of this work should be done with the people who are in the system or community. Ideally, this should happen to a reasonable extent, because otherwise, you’re positioning yourself as an outsider, looking in from a distance. And the reality is that doing this from the outside, without involving the people in the system, not only does a disservice to them, but it also means you likely won’t understand what’s really going on. You can’t see everything that’s happening without being there or talking to those who are living it.

J: That’s great! I really love the way you’ve differentiated between the proxy and the diagnostic, and not expecting one to do the work of the other. I think that’s a really helpful framework.

I know you help people build that overall system view. From my experience, there are a couple of different approaches to take — one being understanding system effects before diving into the details of the system itself. I’d love to hear more about your experience with that approach.

Also, I wanted to dive into some of your worksheets and processes, especially around how you guide people to start with problems, move toward identifying patterns, and then shift into possibilities. It was fascinating to see how you use that framework. I’m curious to hear more about how you arrived at that three-step process, and if you have any best practices for people who might want to apply this in their own work or community, how they can do that in an effective way.

M: Yeah, so what you’re referring to is the Problems to Possibilities Canvas, essentially a worksheet. It’s, in part, a reflection of a lot of the work we’ve done with organizations and communities, helping them conceptualize their systems and then figure out the next steps.

The value of methods like social network analysis and other technical approaches is that they provide a lot of data and insights. However, the challenge with these methods is that they still require the right volume of data, a sufficient level of completeness, and all the necessary factors to be truly effective. Even if you have most of the data for something like network analysis, you’re still only getting a slice of the whole picture. It’s not fully comprehensive, and it has its own limitations. So instead of seeing it as the only approach, the Problems to Possibilities approach is designed to be more free-flowing and accessible.

It’s not meant to be a back-of-the-envelope exercise, but more of a self-facilitated process that allows people to work through things. Network analysis, while valuable, can be quite technical and requires specific conditions to do it well, as well as time and resources to interpret the results. In contrast, this approach doesn’t always need that level of investment and allows for a more flexible exploration of the issue at hand.

The Problems to Possibilities approach emerged from the concept of soft systems mapping, like rich picture-style maps, where people can visualize what they’re thinking about. The goal is to help them get those ideas out of their heads and onto paper, constructing a mental model of the situation. However, we intentionally framed it as a Problems to Possibilities approach to narrow the focus a bit.

We start from a deficit position because the conversations that sparked this process often began with people saying, “We want to address X problem,” whether it’s family violence, youth obesity, vaping, or drug use. The goal was to focus on a problem they wanted to fix, and to apply systems thinking to do that. This is a self-facilitated process designed to help people unpack the issue in a manageable way. It’s meant to break down the process for those who might be familiar with systems approaches but may struggle to apply them effectively.

The first step is to conceptualize the problem as a system. So, you start by writing the issue in the center, then identify the different factors causing it, and explore what causes those factors. You draw the links between them, and then step back to interpret the patterns. For instance, you might think the issue is that young people lack motivation to be physically active, but after mapping the factors, you realize the real issue is access to physical activity opportunities, not motivation. This reframing, from a motivation problem to an access problem, changes the way you approach solutions. Instead of focusing on motivating kids, you’re now thinking about how to improve access to physical activity opportunities.

Now knowing that access is the core issue, the next challenge is figuring out how to improve it. This is where the second stage of the process comes in. We approach it almost like a logic model, but with the aim of positioning the problem you’ve identified not as something surface-level, like “kids are just lazy and don’t want to be active,” but rather as a deeper systemic issue.

Then, we shift to think about what a highly accessible system or set of opportunities for young people in the community would look like. At this point, we have two bookends: where we currently are, and where we want to be. The next step is to figure out what feasible actions or steps sit in the middle that we can work toward.

The language used throughout this process is meant to be very accessible and aspirational, but also realistic. It acknowledges that there are multiple steps to go through before you can even reach a point where you can start answering, “What is the real problem we want to address?” and “What can we reasonably do about it?”

If time and money were limitless, there’d be a lot of things you could do. But in reality, depending on your position in the broader system, there are often constraints and limits. The process helps you justify why you can’t pursue certain actions, and instead focus on what you can do now. For instance, you may have to start with a smaller or more feasible intervention — Y — instead of jumping directly to a bigger solution — X.

J: I really appreciate the encouragement to check out that resource, especially with the different metaphors you’ve used, like the idea of dropping a stone and watching how it ripples. Or the concept of trying on opposites instead. It’s so effective! And the simplicity of the language is refreshing — there’s often so much jargon when it comes to entering the world of systems thinking, and it’s nice to have something that feels more approachable and doesn’t turn people off right away.

M: I have to admit, anytime I introduce people to systems concepts, I always start with a metaphor. It’s just the easiest way in, because you can draw on things everyone’s experienced. Like, everyone lives in their own body, so they can relate to the idea of the body as a system — maybe you’ve got a sore spot here, but it’s actually caused by something else entirely. Or, like you said, the idea of ripple effects… or planting a seed and watching a big tree grow.

Those kinds of metaphors reflect what the more technical language in systems thinking, like leverage points, cascades, tipping points, is really getting at. But that language can feel pretty inaccessible unless someone’s already deep in the space or has time to explore it. And I think that’s always the tension: as experts, we try not to forget that. You need those simple entry points so people can self-facilitate, because you’re not always going to be in the room with them.

Having tools that work at different levels, like temperature checks or self-facilitated processes, those aren’t the answer, but they are ways in. They help people get started in a field that’s dense, big, and still evolving.

And honestly, that’s before you even get into all the different types of systems mapping approaches or systems dynamics models. What I’m talking about still sits pretty firmly in the soft systems space.

So yeah… start simple. That’s really the key.

J: Gotcha! Let’s shift gears into the System Effects approach. Could you walk us through the essence of that method? Maybe talk about when you tend to turn to it, and how you think about its role compared to other approaches.

It’d also be great if you could give us a sense of what it actually looks like in practice — both in terms of community involvement and the level of lift it requires from your team. Basically, if you could just give us a bit of a tour of how you use System Effects, that’d be great.

M: Absolutely. I first came across System Effects through Dr. Luke Craven, who developed the approach. As PhD students do, Luke had published some papers, and one of them focused on this hybrid methodology for understanding food insecurity. At the time, I’d been working in the social network analysis space for a while, and when I read his paper, it really caught my attention. I thought, “This is genuinely interesting.” So, I jumped on LinkedIn, sent him a message, and basically said, “I read your paper. I love it. Let’s be friends.”

I know you’ve had Luke on this podcast, so listeners may have already heard him explain it in detail. But for me, the part that stood out — and still does — is how the maps in System Effects are generated. In most partnership or network analysis work, the typical approach is pretty structured: you ask someone from an organization, “Who do you work with, and on what?” You end up with a series of process and relationship questions — “How strong is your connection?”, “ How well does it function?” — that tend to frame everything as if these dynamics are entirely objective and easily measurable.

That’s where I always felt some tension. Those types of questions can oversimplify complex realities. What I appreciated about System Effects is that it moves away from just mapping formal relationships. Instead, it focuses on capturing an individual’s lived experience of a complex issue, looking at either the upstream drivers or the downstream impacts of that issue on them personally. That shift in perspective feels a lot more powerful and meaningful in understanding real-world complexity.

For example, we might ask something like, “What are the systemic barriers to you being physically active while you’re at school?” I ran a project in the ACT that explored exactly that; looking specifically at the barriers preventing secondary school students from being physically active during school hours. We spoke with a few hundred students and asked them directly: “While you’re at school, what stops you from being active?”

The responses were telling. Some students said, “I want to hang out with my friends. I don’t want to run around — I’d rather sit and chat because I haven’t seen them all day.” And when you dig a little deeper, the reason for that was pretty simple: they value those friendships and want to stay connected with what’s happening in each other’s lives.

What I find really valuable about System Effects — and how it differs from other mental model mapping approaches — is how it takes these kinds of individual maps and systematically aggregates them. The process uses a mix of thematic analysis and quantification, weighting the connections based on how many people drew similar links. So you can move from hundreds of individual maps to one consolidated system map, built around thematically analyzed factors.

The benefit of that is twofold. First, it lets you build a narrative about how a system functions in a specific context. In this case, we could say, “Here are the systemic barriers to physical activity as identified by students within this particular school community.” Second, it gives you a way to look at perspectives across different groups. For that project, we also included teachers. It wasn’t so much about comparing their views directly, but about exploring how teachers’ perceptions of student barriers aligned, or didn’t, with what students themselves identified.

The really valuable aspect of this approach is how it brings in the lived experience dimension, which I think is critical. It allows you to incorporate everyone’s personal experience of an issue, even acknowledging that some people’s perspectives might be outliers compared to the majority. But those perspectives still count. Even if you’re the only person, out of a hundred participants, who identified a particular link, that insight is still valid and recognized. It’s just placed in context: noted as less common, but no less relevant.

We’ve used this process a few times now, often as a way to help groups understand a particular issue. When people come in asking, “What are the barriers?” this gives them a structured way to actually answer that question, and do it in a way that values both the common patterns and the individual nuances that might otherwise get overlooked.

The most recent example that I really want to highlight, which just launched this week (April 2025). We used the System Effects process to examine the drivers of poor lawyer wellbeing. There’s been plenty of research showing that lawyers tend to have higher rates of psychological distress and mental ill-health compared to the general population and other professions. But rather than just repeating that research, the focus here was different. They wanted to ask, “If we already know the factors, and the research has been piling up for years, what we’re still missing is understanding how these factors actually relate to each other.”

So, we applied the System Effects approach with around 1,100 lawyers completing the survey. From that, we identified 45 different factors contributing to poor wellbeing. What made this unique was that we didn’t start from scratch. The framework we used to code the data was built on top of the existing body of research. We blended that with participants’ lived experience. Even so, out of those 45 factors, 25 were new, things not previously captured in the literature. That really underscored how even the best research tends to leave gaps; you’re still only ever seeing pieces of the puzzle.

For example, some factors like “workloads” are always present in previous studies. When people talked about having too much work or lacking support for the workload, we’d group those responses under a common theme. Different ways of describing the same problem still pointed to a single factor. And with a dataset of this size — 1,100 responses out of roughly 29,000 registered lawyers in Victoria — we had a strong enough sample to make some generalizations across the sector.

What we ultimately found is that poor wellbeing isn’t a single problem. It’s the outcome of dozens of interrelated problems. The real issue isn’t that lawyers experience mental ill-health, it’s that there are 45 distinct drivers that interact differently for every individual, combining to create that outcome.

For the sector — through a cross-sector initiative led by the Victorian Legal Services Board — we reframed the challenge: the problem isn’t lawyer wellbeing; the problem is 45 systemic issues. That became the foundation for developing a theory of change model. And while theory of change is quite similar to a logic model (both help chart a path from where you are to where you want to be) the emphasis here was on being really clear about why you think certain actions will actually work.

From there, we moved into workshops and other activities, but it was never about asking, “How do we fix wellbeing?”. Instead, it was about breaking it down into the real issues underneath: How do we support lawyers to manage their stress? How do we improve the quality of managerial support and communication? How do we reduce competitiveness between lawyers working on the same team? How do we make sure the sector itself is supporting lawyer wellbeing, rather than reinforcing harmful dynamics?

We kept coming back to the fact that yes, there are 45 distinct problems, but they’re interconnected. So, we can’t just pick one and hope that solves everything. It’s about recognizing that meaningful change will require addressing multiple issues concurrently, or at least being mindful of how they link together.

What made this work powerful wasn’t that we uncovered some brand-new problem no one had ever seen before. Everyone already knew lawyer wellbeing was a serious issue, as the research has been saying that for years. The real shift was in reframing the problem: moving from “lawyer wellbeing” as a single issue to seeing it as the product of 45 interrelated factors.

At our launch event, where we had around 60 sector leaders, including CEOs and law school deans, the reception really reinforced that we were onto something important. People recognized this wasn’t just repeating what they already knew. It gave them a new way of seeing the issue — a perspective that could potentially move the dial on something that, until now, has felt stuck. Because when you treat it as a single problem, you fall into that pattern of thinking, “Oh, lawyers are experiencing mental ill health; they need to see a professional.” And that’s really just treating the symptom, not the cause.

That’s why centering lived experience and using a systemic approach like System Effects was so powerful. It shifted the whole conversation away from symptoms and toward understanding the deeper systemic causes.

J: Yeah, and maybe let’s wrap up on that point. When you think about the process, there’s a clear difference between the moment when you’ve finished collecting data with the System Effects survey and produced the network map, and the work that follows after that.

So, let’s say you’re at that point where you’ve got the visualization in front of you and maybe you’ve even run some metrics — great. But what are you actually paying attention to in that view? What do you look for in the network itself? And then, what’s that additional scope of work that your team takes on, that next phase that moves beyond just showing the map? How do you help bridge that gap between having the insights and turning them into something actionable, like the launch itself or the set of recommendations that come out of the process?

M: Yeah, like I mentioned earlier, the main product coming out of the process was this model that outlined the outcomes we’d need to work toward in the short, medium, and long term to move toward that aspirational future. And, importantly, we reframed the problem itself. Instead of seeing it as one issue, we identified 45 interconnected factors and mapped the relationships between them.

What’s really powerful, especially with a dataset that includes insights from over a thousand individuals, is how we can use network analysis to examine the influence those factors have on each other. So, it’s not just about showing a visual map and saying, “Wow, this is complex.” It’s about figuring out, where do we start? Out of the 45, what are the top five or ten factors we could realistically begin working on that might create meaningful change?

Now, there are lots of different network analysis metrics you can use. The challenge with this particular project was that the map was so dense that some metrics weren’t all that helpful. It’s like, yes, technically everything’s connected, but that doesn’t tell you where to start.

What we settled on was a specific centrality measure that highlights factors acting as bridges between other elements in the network. We weren’t looking for the single most “upstream” cause. Instead, we focused on the factors that most frequently sat at the intersection of everything else, the ones that link multiple other issues together.

Those bridging factors offer the greatest opportunity for ripple effects. If you can positively influence one of them, say, improving managerial support, our assumption is that it would cascade out to impact related issues like workloads, stress levels, workplace culture, and team dynamics. We may not know exactly how all those effects will play out, but that’s the strategic bet we’re making by targeting those central connections first.

What was particularly interesting during this process was the influence of the 45 factors we identified. Workload stood out as by far the most influential factor; three times more influential than the next highest factor. But this presented its own challenge. While the map clearly indicated that workload plays a central role, it didn’t provide a clear solution. It’s not enough to simply say, “Workload is the problem.” The real question was: how do we address it? We know that workload is influenced by many other factors, so we needed a way to break this down further.

To tackle this, we stratified the 45 factors across a socioecological model of health: individual-level, interpersonal, organizational, and sectoral factors. We then reran the analysis to better understand which factors within each category were most influential. For example, within the interpersonal level (the relationships between individuals), we identified about eight or nine key factors. By applying the same centrality metric, we were able to pinpoint the most influential factors in each area.

This process helped us create more manageable subsystems, which was crucial for providing actionable insights. It allowed us to narrow down the 45 factors to a more focused set of around 15 that were particularly relevant for organizational leaders to consider. This doesn’t mean the other factors are irrelevant, but for someone in a leadership position, these are the factors to focus on first. For entry-level lawyers, it was a similar process — we identified individual-level factors they could take action on in their own lives to address issues like stress or workload.

Ultimately, this approach helps avoid overwhelming people with too much responsibility. It’s about giving individuals a clear sense of what they can control within their sphere of influence. Whether you’re an individual lawyer, part of a team, or leading an organization, you can focus on actionable steps within your role and make a meaningful impact.

It really comes down to reinforcing agency. When people feel they have a level of agency, they’re more likely to take action. This approach clarifies what actions people can take at different levels — individual, interpersonal, organizational — and that sense of agency is what drives real change.

J: Well, Matt, thank you. Finally, could you share a bit about what type of clients are the best fit for First Person Consulting? Specifically, if people are struggling with certain challenges or focusing on particular areas, who would be the ideal clients for FPC?

M: That’s probably the hardest question you’ve asked me! We’ve always positioned ourselves as a team that wants to work with others who are grappling with tough challenges. If you’re dealing with something complex or difficult, that’s usually where we start.

I often describe our value proposition through a reference to a UK comedy show from the late ’70s, early ’80s, called “The Goodies”. They had a tagline in the opening credits: “Anything, anywhere, anytime”. That’s kind of how I would describe our approach.

But really, the people we love working with are those tackling environmental, social, or public health challenges. Specifically, we focus on the big questions like: “Where do we start?”, “How do we know if it’s working?” Or even bigger, “Are we focusing on the right things?” We don’t really limit ourselves beyond that. Everything is interconnected. Something is never just a social problem, it’s often an environmental or health problem as well.

J: How much do you typically focus on a specific geographic area in your projects versus taking more international or global projects?

We’re all based in Australia, in the southeast corner, but to be honest, we work pretty much everywhere. I’ll admit, though, that most of it is virtual these days. We don’t get the thrill of jet-setting around the world anymore.

We do a lot of advisory work with organizations, and nowadays, many of them recognize the need to build internal capabilities. So, we’re shifting toward focusing more on capability-building partnerships. We try to move away from the traditional model where it’s like, “Here’s a program we need to evaluate in a fixed way,” and instead take a more flexible, collaborative approach.

For example, we do a lot of work with Movember, the global men’s mental health and physical health charity. So, we’re not restricted by geography. Time zones, however, are my biggest limitation. We usually find a way around that though, or at least make the project compelling enough to get me excited to stay up until 1am for a virtual presentation!