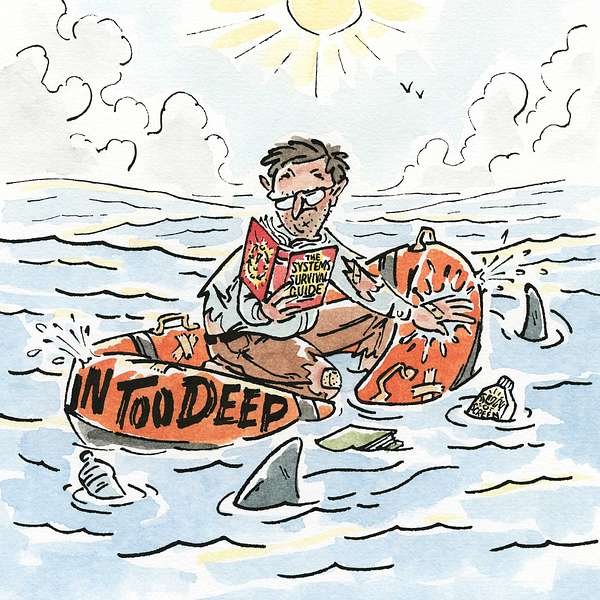

In Too Deep

We explore how changemakers across the globe are engaging complexity to tackle tough issues. Created by the team at Kumu.io

In Too Deep

Creating new patterns for learning and leading | Episode 14

What patterns are shaping how we learn, lead, and live, and how might we begin to shift them? In this week’s episode, we’re joined by Jessica Kiessel from (Re)Patterning Lab. Jessica stewards spaces and builds infrastructure to support the learning, creativity, and shapeshifting needed to live into the patterns we hope to see in the world, both for individuals as well as inside organizations.

Tune in to explore more around:

- Seeing and making patterns

- Building containers for learning

- Poking at our perspectives

- Creating conditions for curiosity

If you're curious about reimagining leadership, learning environments, and the patterns that shape our lives, this episode is for you! Subscribe to the In Too Deep Podcast or read the full transcript on the In Too Deep blog.

Want to go deeper?

To explore art and writing from a growing community of contributors exploring pattern making in their every day lives, visit www.patternmaking.org. To learn more about Jessica's organizational patterning work, visit www.repatterninglabs.org . In particular, we recommend you explore the beta version of common organizational patterns, an entry point for folks working in dominant culture organizations to work with patterns. If you are interested in collaborating or engaging with Jessica, reach out through either site or contact her on LinkedIn.

Jeff Mohr (JM): Thank you, Jessica, for being with us today. I’d love to start by giving you a chance to introduce yourself and share a bit about your background.

Then, I’d really like for you to take us back — can you recall the first time you felt like you were stepping into something more complex? Whether we call it systems thinking, a shift in awareness, or simply seeing the world differently — was there a moment when that way of seeing things became part of how you moved through the world? Maybe it’s something you’ve always carried with you, or maybe it emerged at a certain point. We’d love for you to take us through that journey.

Jessica Kiessel (JK): Great, yeah. I’m Jessica Kiessel. I’m based in Seattle now, though I grew up in Northern Michigan. These days, I’m doing a lot of experimenting across different spaces. I’m an artist — I teach ceramics in West Seattle, and I also create my own sculptural work.

Alongside that, I do some consulting, mostly accompanying folks in learning, strategy, and evaluation roles — really, anyone in leadership who’s trying to move in more systems-aware, complexity-conscious ways.

I’m also stewarding a nonprofit called (Re)Patterning Labs, which is kind of a container for a lot of these experiments. Within that, there’s a community I hold with others — people I think of as pattern-makers. They’re writers, artists, people exploring how to reconnect the way they live with who they want to be in the world. It’s very much about reconnecting with purpose.

And I have these ongoing curiosities, like: how do we actually walk inside our organizations in the patterns we want to see in the world? How do we live those values from the inside out?

Sometimes it feels like I’m doing too many things — but then I realize it’s all connected. It’s really just one thread running through everything I do.

JM: Wonderful. And I’d love to hear a bit about how you came into working with complexity. Has that always been a part of how you’ve seen the world, or was there a moment — or maybe a series of moments — when that awareness started to take shape for you?

JK: I had a pretty complex childhood. My parents divorced when I was young, and then each of them remarried and divorced again. They were really different people. My mom is an artist, and when we were kids, we spent a lot of time with her reading and talking about art. Looking back, I wouldn’t have described that as a “complexity” approach at the time — but now I can see how that experimental way of working, and learning to trust a kind of somatic knowing, was foundational. That ability to feel something deeply and try to articulate it — that’s been important to me all along.

Then I’d go to my dad’s house, and he was much more outward-facing and extroverted. I think moving between those two environments sparked a curiosity in me about people and how different ways of being shape how we relate to the world.

I also tend to think in shapes. So when I’m in social situations, or thinking about organizations, I often see them as forms or patterns — which I think connects to this way of sensing complexity.

Spending a lot of time outside as a kid also played a part. I grew up in the woods, and that connection to nature gave me a way of feeling into systems, even if I didn’t have language for it. Later, I studied anthropology, which made sense given all that.

As an adult, I found myself in international development spaces that were often trying to oversimplify everything — reduce things down in a way that didn’t feel right. It wasn’t until I connected with the Omidyar Network that I realized: Oh, this way of being that feels more natural to me — that’s actually a complexity-aware, systems-thinking way of being.

That realization only came about five years ago, when I finally had a name for it. I think that’s true for a lot of people — we’re often living in these ways already, but we’re taught to cover them up or make ourselves fit into more conventional roles. I definitely did that — trying to be a “good” management consultant. But over time, we learn how to be more fully ourselves.

JM: Yeah, I hear you. It’s like sitting in the dissonance, right? Like, this doesn’t feel right — almost as if it’s not living in integrity by not being able to lean into that. That really feels very present.

JK: Yeah! Well, I will say that sometimes we just need to get paid. So we can decide “Yeah, I’ll bend over backwards if you want to pay me”. But I think it takes time to build confidence, especially in a culture that values evidence-based success. It can be a bit difficult to feel open and confident in things that may be considered a bit strange or uncomfortable at first.

JM: I’d love to circle back to the concept of ‘(re)Patterning labs’ and dive deeper into the idea of patterns and patterning. Could you share when and how you first encountered this language? What does it mean to you, and how does it shape the way you approach complex awareness and systems thinking in your practice?

JK: When I joined the Omidyar Network, I immediately felt like this paradigm shift was right. But as I dove in deeper, I realized that much of the conversation was around systems thinking, and honestly, it felt a bit abstract and foreign to me — like I was speaking a language that wasn’t my own. That’s when I started hearing more about patterning, and it clicked for me. It was through a paper by Ingrid Burkitt and a conversation I had with Heidi Sparks Goober, the founder of Emergent Learning Community, that it all fell into place. The concept felt very visual and tangible.

Looking back, I’ve always been aware of patterns, but it wasn’t until then that I really began adopting that specific language. A huge breakthrough for me was realizing that I could explain this to my family in a way they understood — something I often struggle with. When I’d talk about things that worked in my life, they’d just respond with, ‘What are you talking about?’ But when I started talking about patterns, it resonated with them.

The more I thought about it, the more I saw how patterns are everywhere — especially as an artist. We’re naturally drawn to patterns, and often, what we consider beautiful is rooted in these common, recurring forms.

I have this vivid memory of sitting with my mom in the Midwest. Growing up, I was being trained to be a ‘good Midwestern housewife,’ which meant learning how to sew. My mom taught me that, while patterns are important, a skilled seamstress would adapt the pattern to fit the person. She was curious about the people making patterns, because, historically, women didn’t buy patterns — they made them. If you made a dress and wanted to recreate it, you’d figure out how to copy it.

She’d talk about pattern makers as women who look into the future and imagine what others might want, and make it easy for others to follow and to fit many bodies. This idea stuck with me because it spoke to the broader patterns we see in life, especially the dominant ones we often fall into, without meaning to.

Like when I was becoming something like a management consultant — I didn’t really want to go that route, but it was just ‘what you did’, what was expected. But the more I embraced the idea of choosing to move differently, the more powerful this language of patterning became for me. It felt not only resonant but also easy to adopt.

JM: That really resonated with me too. I remember reading that and realizing that the first step — recognizing patterns — was something I hadn’t fully thought through. I hadn’t considered the idea of designing patterns, or doing so in a way that’s flexible and adaptive.

Can you share more about your journey with that? When you think about designing patterns, how does that play into your work, whether in the social change space or elsewhere? How does this approach support you and guide your actions when you’re working in those contexts?

JK: It’s interesting because we often talk about behavioral patterns — things like, ‘I should wake up and run in the morning’ — and how building those habits can shape us. And then we talk about larger societal patterns, like how capitalism is damaging our world. But I’m really interested in the space in between, the day-to-day interactions we have with other people, especially in smaller teams. These smaller social interactions are incredibly powerful and, over time, they shape our lives in ways that eventually add up to larger patterns.

For me, that in-between space is where a lot of transformation happens. I’m quite self-reflective, and that’s something I’ve developed over time as a way of navigating the world, which is so different from how I grew up. When I look back at my younger self, I can see patterns where I was in leadership roles, where I was expected to have the right answer — and so I would just provide it. But eventually, there comes a point where that just doesn’t feel right. You start questioning, ‘Why am I defending this?’ and in those moments, I realized there’s a choice. You can decide to take a different direction, and that’s when I began to see how much agency we have in shifting these patterns.

For me, it’s really about reflecting on where we have agency within these patterns. We can get caught up in them, but the key is knowing how to step back, how to ‘begin again’ when things feel off. I’m really interested in these micro-movements — how we can help people navigate complex environments and find their agency within those situations. When we do that, we can start to reshape the patterns, both for ourselves and in the broader systems we’re a part of.

I’ll share a story about an interaction I had with a colleague while working at the Omidyar Network. In my role as someone focused on learning, I was often seen as being in service to others — coming into a team and asking, ‘What do you need?’ I naturally lean into caregiving, spending a lot of time thinking about how I can support the team.

But one day, a colleague flipped the script. They asked me, ‘What are you learning? How can I help you?’ And it completely changed the dynamic. Suddenly, it wasn’t a one-way relationship where I was simply supporting the team — it became a mutual exchange. They were genuinely curious about how they could support me too.

That small moment really struck me. We make these little decisions in our daily interactions, and they can have a big impact. It’s not just about whether we’re individually doing the right practices or taking care of ourselves — though that matters too. It’s also about how we shift the nature of our relationships and the ways we work together. These micro-shifts can reshape the patterns we’re part of, not just personally, but collectively.

JM: I agree. That shift you mentioned, from servicing to something more mutual, really resonates. For me, it feels like a movement from something extractive to something generative, where the relationship actually starts to work in a deeper, more reciprocal way. That story really brings it to life.

I’d love to spend a little time in the space of learning, because I think it’s something we talk about a lot, almost casually. We say we’re ‘learning,’ but often it feels like we assume it just happens automatically or that we already know how to do it well. And yet, I think your experience in exploring and shaping the proactive patterns around how we learn — especially in complex spaces — is so valuable.

So I’d love to hear how you define learning. What does it look like when we’re really doing it well, especially in environments that are complexity-aware or constantly shifting? And if you have any stories that show how we sometimes get in our own way — like habits or assumptions we might need to unlearn in order to actually learn — I’d love to hear those too.

JK: First off, I’ll admit — when I first joined the Omidyar Network, even though learning had always been an implicit part of my work, I had never formally been ‘the learning person.’ I was honestly pretty intimidated by it. Early on, I was introduced to Marilyn Darling and the Emergent Learning Community, and one idea that really stuck with me was this: learning isn’t something theoretical you put on a shelf. It’s not abstract. You’ve truly learned something when it changes how you act and you see a different result because of it. That felt really grounding to me.

That framing is so important because it helps us focus. Sure, we could technically learn about anything, but why learn French if you’re never going to speak with a French person? Learning becomes more meaningful when it’s tied to something you’re actually doing or caring about now — something you can actively experiment with. That could be on a personal level, or even on a societal level, depending on what’s most relevant.

One of the biggest challenges I’ve run into is realizing that we can’t learn for other people, and we can’t make people learn things. That was a hard lesson for me. As adults, most of us learn through experience, through engaging with what’s directly in front of us. You can set the table beautifully — you can say, ‘This is important,’ and make all the resources available — but if the learning isn’t connected to something that feels personally relevant, people just won’t absorb it. They won’t feel it in their bodies in a way that lets them move forward with it.

Photo by Nick Fewings on Unsplash

Once you accept that you can’t control other people’s learning, everything changes. Your role becomes less about transferring knowledge and more about creating the conditions — the space — for people to access, discuss, and explore the questions that matter most to them. You hold space for that exploration.

What I see a lot is this tendency to oversimplify or pre-package learning because, understandably, people are busy. But that often misses the depth people really need. We learn through patterns, through stories, by making connections. If you don’t reveal what’s underneath — the ‘why’ something matters — it just doesn’t resonate in the same way.

So yeah, I think a lot of the missteps come from this idea that learning is something we can mandate or deliver in isolation from what people are actually feeling or grappling with. Real learning is much more emergent and embodied than that.

JM: Yeah, and I’d love if you could walk us through what it actually looks like when you’re supporting a team. Like, to your point about micro-moves — what are some of the specific habits or practices that help a team build a more robust learning culture? Is it something like a weekly meeting? And if so, what kinds of questions are being asked in that space?

More broadly, what are some of the concrete practices or patterns you’ve found that really support people, give them guidance, and help deepen their learning in a meaningful and effective way?

JK: Yeah, I’d say one of the most important things, to start, is making your assumptions about the world explicit — just naming them without judgment. As a learning person, I often ask questions to help surface what people are already thinking. Once those thoughts are out in the open, we can sit with them and gently poke at them: Are they still true? Is there evidence that challenges them? Could we get new perspectives that deepen or expand the picture?

I think we often limit what’s possible by judging our initial thoughts too quickly. But if we see our current knowledge as just a snapshot of where we are right now — something that will naturally evolve — we can be more open. Making our thinking visible allows us to build on it. We’re often noodling on things subconsciously, even dreaming about our learning without realizing it. So when we name things, we start noticing them differently.

If you can get your thinking out there, then you can create spaces to reflect on it — to actually test and refine that thinking. And that needs to happen across levels. At the individual level, it could be as simple as taking a moment after a meeting to jot down the three things that felt most important. Or taking 10 minutes at the end of the week to reflect. That kind of spaciousness — both in time and in mental pace — is key. We’re all moving so fast, and sometimes we just need to step out of the river for a bit.

At the team level, there’s also this dynamic where people can be hesitant to share. Maybe they don’t think what they’re learning is important, or they don’t feel like it’s fully formed. But if we don’t share our stories as we go, we miss out on the chance to learn from each other’s experiences. So building in team practices where people are encouraged to talk about the questions they’re sitting with, the challenges they’re facing, and get multiple perspectives — that’s where real learning can happen. And the same goes for partners and grantees. That kind of reflection space isn’t extra — it is the work. Because otherwise, you just end up repeating the same patterns.

Now, one challenge in learning roles is the pressure to show outcomes — like, “What changed as a result of this learning?” That can be useful, but people also often act on learning without realizing it. And that’s okay. Documenting it can help others see the shift or come along with you, but it doesn’t have to be rigid.

I don’t believe there’s a one-size-fits-all cadence either. Some things move fast and need real-time reflection; others move slowly and need more space. If you’re dealing with long, complex challenges, daily reflection can feel exhausting and misaligned. But if you’re in a crisis and only reflecting once a year, it’s too late. So ideally, your reflection cycles should match the rhythm of the work.

JM: You mentioned learning in collaboration with grantees and partners — are there any other things you’d highlight around that? Especially when organizations are trying to move strategy or process beyond their own walls and into broader communities.

How does learning work well when it’s held across a network or with a more diverse group of stakeholders? What helps it actually land and be meaningful in those more complex, distributed spaces?

JK: Yeah, like I said earlier, you really can’t control what people learn. And I think that’s especially true when you’re trying to do learning in community or across a network. If you’re going to hold learning in that kind of shared space, it has to be genuine. It has to be grounded in real relationship, not just a set of expectations.

Sometimes, the people you’re engaging with might not be in a place where deep reflection is even possible. They might just be trying to get through the day. And I think we have to recognize that. Learning can actually feel oppressive when it’s forced or mandated — especially if people aren’t resourced to engage with it.

So part of the work becomes asking: what conditions need to exist for people to have enough space — enough breath in their lives — to be attentive in this way? And that brings up a real equity question. Like in my own life, my partner has a job with health insurance, and that gives me a bit of room to take risks and reflect. That kind of stability matters.

Many people don’t have that, especially in the communities that funders and nonprofits aim to support. So if we want learning to really happen in more distributed or community-based settings, it requires funders and institutions to ask: are we sharing power and resources in ways that create spaciousness for others? Are we creating the same conditions for reflection that we enjoy ourselves?

And when people do have that space — when they’re not just trying to survive — they absolutely will learn. They’ll get curious. They’ll reconnect with what matters to them. But when someone’s barely keeping their head above water, it’s hard to ask them to also engage in deep inquiry.

I’ve also seen this play out inside organizations. Sometimes it’s the end of the year, and we’ve got these baked-in cycles — we want teams to reflect and report. But some years, teams just aren’t in a place to do that well. And we have to make space for that truth too.

That’s where compassion comes in. Yes, there’s value in structure and discipline, but there are also times when rigidity just gets in the way of the work we all care about. Learning has to be human. It has to meet people where they actually are.

JM: From my experience with you, it seems like you’ve worked across a variety of organizations and institutions — some big, some small — and you continue to bring that experience into your consulting work. You’ve often been at the forefront, pushing for a complexity-aware or systems-thinking approach. So, I’d love to hear from you: what are some of the ongoing barriers you’re still encountering that block those approaches from being fully realized?

I know we’ve had some conversations about governance being one of those challenges, so maybe we can dive into that. But to start, I’d love to understand more about the key obstacles you’re facing as we try to integrate complexity and systems thinking into areas like strategy and learning. What’s standing in the way?

JK: I’ve come to accept that I have a lot of energy around getting curious about where there’s stuckness or misalignment, and that can sometimes get me into trouble. But I also have a deep compassion and love for people, and I think it’s so normal to encounter these challenges. I grew up in a context where people made a lot of mistakes, and I understand that good mistakes happen to good people, just as bad mistakes happen to everyone. It’s part of the process, and it can feel very shameful to find ourselves in a place where we’re being called out or asked to change.

People in leadership positions, in particular, often aren’t in control of their day-to-day lives. They can be very removed from the things they’re responsible for, which creates a precarious feeling. It can make them risk-averse, reluctant to be vulnerable, and afraid of exposure. And, as I mentioned earlier, those aren’t the conditions for flourishing or learning.

So my challenge has been recognizing that the power dynamics within hierarchical organizations can often drive disconnects that hinder learning and adaptation. People individually care — they want to show up differently — but they often get pulled back into old ways of working despite themselves.

I don’t think I have a magic answer, but I’ve been experimenting with ways to help people approach each other with more compassion in those dynamics. For example, you might see a board member who feels set up to make a decision, but they’re only stepping in because, as a leader, you’ve placed the burden of decision-making on them. That’s when you get undercut, and those old dynamics resurface, even if that wasn’t the intention.

For me, it’s really important to have these kinds of conversations. We only have one life, so if we’re not going to address the things that aren’t working well between us, how can we ever move forward? Personally, I’m not afraid of those conversations. They’re essential if we’re going to move through this stuff and learn.

JM: You’ve captured an essential dynamic here, which is being willing to have those conversations while assuming good intentions. When you’re both clear that, hey, something isn’t meeting what we think is a ‘shared standard’, so how can we address that? And this circles back to the learning piece — it’s an opportunity for us to learn how we need to be supported and what conditions we need to thrive.

Now, let’s dive into governance. I think this is particularly relevant because so many people turn to systems mapping, using platforms like Kumu, and other tools to design better strategies. I’d love to continue that thread and think about what you’ve experienced when it comes to strategy approval within an organization or community, or just aligning on priorities. How do we have those conversations in a healthier way?

Where are we still showing up with old patterns that start to suck the energy out of holding things in a more complexity-aware way? And what should we be questioning or letting go of if we’re aiming to move toward more effective approaches?

JK: One thing I’d highlight is that when you zoom out to look at the whole picture, it’s easy to become flooded with choices, desires, and possibilities. You might envision a future that stretches out 40 years, or even centuries, and you want all of that to happen at once. But I think it’s important to be really thoughtful about how we zoom back in and focus.

Yes, this is the picture of what we want, and by having a rich picture of the whole, we can walk forward in alignment. But we won’t feel the conditions of abundance unless there’s some sense of scarcity. Just like you need banks on a river to feel flow, or a vessel to overflow — you need some focus to do that work effectively.

When you zoom in, it’s essential to remember that you only know what you know right now. And as you move forward, that will change. Writing things down — simple causal statements about what you’re observing — helps you reflect and adjust as you learn.

For me, this process of zooming out and zooming in is crucial, but I find that zooming in is really hard. That’s where decisions need to be made, often involving compromises. Leaders may have to take on roles they’re not comfortable with, setting boundaries and renegotiating lines.

I don’t have a magic solution for this, but I do think one of the biggest mistakes I see in systems work is the tendency to see it as either/or. Either you focus on one thing or the whole. But really, it’s about recognizing that to do the work, you have to focus in. That doesn’t mean ignoring the whole. Because what you focus on can shift over time.

JM: Gotcha. Yeah, focusing on that while maintaining the broader awareness is a great point. I know you’ve been involved in a number of processes where you’ve actually created systems maps. How have you seen that evolve over time? I know a common criticism is that these processes can get pretty wonky, and it can be a real challenge to even get to the systems map.

How has your practice evolved in that space? Are systems maps still useful in your experience? How do you tend to approach them now, and what have you found really works well to bring people along in those processes?

JK: I’m actually pretty agnostic when it comes to the tool. For some, maps are incredibly helpful; for others, you might not need a map at all. You could just have a list of statements with assumptions, and you might draw a map later. But for some people, the map just isn’t the thing they need.

What’s really important, though, is being as explicit as possible about what you ‘know’ in a certain moment. That said, what I think is crucial is not presenting it as the ‘truth’. Whatever you write down, it’s not the truth for a lot of reasons. First, because the world is impermanent and things are always shifting. Second, because you only have the perspectives you have — there’s always more out there that you can’t capture.

But just because it’s not the absolute truth doesn’t mean you shouldn’t have the map. Otherwise, everything will just feel like it’s flying around. It’s helpful to have something that holds still so that you can have meaningful conversations and return to what you’ve learned.

For me, the big challenge has been understanding that it’s really about the process of alignment and making things explicit. That process is valuable in its own right. But it’s also important not to treat the map as something to be hung on the wall as if it’s finished work. No, it’s just a snapshot of where you are right now, and as soon as you step out the door, things will change.

That takes trust. Honestly, when I was working at the Omidyar Network, I was really grateful because the work we did with teams was available to everyone in the organization. But it was messy — it wasn’t meant to be presented to a board or external audience. It was constantly being used, evolving. I’m grateful that we had the trust of the leadership to say, “We trust that this work is important.” They didn’t need to fully understand every detail, and they allowed the messiness because it more accurately captured where teams were. It also made it easier for them to not feel so precious about updating it.

JM: Gotcha, that’s great. And just to wrap up — when you think about the decade ahead, what kinds of shifts are you hoping to be part of? What are your hopes for the field? Whether it’s within a specific subset you’re focused on, or more broadly — what would you like to see become the new norm?

And with Repatterning Lab in particular, what are some of the long-term aspirations? As you look toward that ten-plus-year horizon, what are you hoping to shape or contribute to?

JK: I think there’s a growing understanding — and I’m putting air quotes around this — of what “new leadership” looks like. A kind of leadership where you let go, where you’re stewarding the conditions for something to emerge. Where you’re taking responsibility for enabling others to take risks, in the spirit of Marshall Ganz. And I think there are some important lessons starting to surface around that.

But we don’t yet have shared norms for this kind of leadership. We don’t know how to hold leaders accountable to it, or how to support them in practicing it. Ideally, it won’t remain a side conversation. Maybe someday you won’t go to Webster’s and find just one narrow definition of leadership — hopefully you’ll see something more expansive. That kind of shift may take more than a decade, but I think it’s worth hoping for. Because our primary mental models shape so much else. And if we can loosen or reframe those models, even slightly, we open up room for meaningful change.

Another thing I’ve been reflecting on is how we carry and share wisdom within the social sector. There’s so much conversation about evidence — what counts, how we share it — but less about the everyday, lived knowledge that actually shapes how people work. I think about the metaphors and phrases that stick with us, what I sometimes call the “pebbles in our pockets.” Those small, resonant ideas that we carry around and return to in key moments.

For me, it’s things like: “beginnings matter,” or “small is all” — that’s adrienne maree brown’s phrase. Or a phrase I used to share with Clara: “feed the learning.” These fragments hold weight. They’re passed between colleagues, across generations, through experience. And I think there’s something really powerful about naming, collecting, and tending to that kind of wisdom — not just as inspiration, but as part of the infrastructure of how we learn and lead in this space.

When I was younger, I often felt alone. I didn’t have access to that kind of cross-generational mentorship or storytelling. So one of my hopes is that we’ll find it more normal — and more necessary — to build those bridges. That we’ll take more seriously the work of stewarding the wisdom this sector holds, and make it easier to share and apply it across time and context.

And finally, I think we need more space for people to make mistakes. One of my favorite metaphors comes from Father Richard Rohr, in Falling Upward. He describes lifelong learning as ice skating — you have to fall on one side to push off in the other direction. That image has stayed with me: the idea that real learning requires falling, and that growth doesn’t happen in a straight line.

But we don’t really teach that. We don’t model it well in schools or in leadership. There’s still this idea of climbing a mountain, a single path upward. And I just don’t think that’s how life — or leadership — actually works.

We also don’t have enough infrastructure for course correction. If you’re in a role or organization and realize you’re out of alignment, it’s often incredibly hard to step back or shift direction. We haven’t built enough systems that support that kind of vulnerability or transition. And yet, if we believe leadership requires experimentation, reflection, and growth, then we have to ask: what are the conditions we’re creating for leaders to actually do that well?

So part of what I imagine, over the next decade and beyond, is a broader understanding of what it means to move through a career or a calling — not as a linear ascent, but as a deeper, more dynamic journey. One that’s responsive, human, and full of learning.

JM: Yeah, it’s such a beautiful vision. And for those who are interested in learning more about (Re)Patterning Lab — or who might want to connect with you directly — could you share a bit about the kind of work you do?

Specifically, I’d love for you to give a quick overview of your consulting practice, particularly around strategy and learning facilitation. Just so folks have a sense of how you work and how they might reach out if they’re interested in collaborating.

JK: For sure! If you’re interested in sharing your writing, reflections, or creative work around pattern-making and how you’ve been wayfinding in your own life or work, I’d love to hear from you. You can visit patternmaking.org and reach out there. It’s a very inclusive space, and we’ll be beginning to host community gatherings soon.

And if you’re more curious about how to start aligning your organizational practice with the patterns you hope to see — essentially letting a bit of light in and beginning to experiment — we’re building something for that as well. We’ve been reflecting on how much we need infrastructure that supports learning over time and across spaces. One thing we’ve noticed is a real gap in accompaniment for people doing this work from inside organizations.

So we’ll be launching some learning cohorts to support that kind of deep, ongoing work. If that resonates or you’d like to learn more, feel free to reach out through repatterninglabs.org.

- To explore art and writing from growing community of contributors exploring pattern making in their every day lives, visit www.patternmaking.org

- To learn more about Jessica’s organizational patterning work, visit www.repatterninglabs.org . In particular, we recommend you explore the beta version of common organizational patterns, an entry point for folks working in dominant culture organizations to work with patterns.

- If you are interested in collaborating or engaging with Jessica, reach out through either site or contact her on LinkedIn.