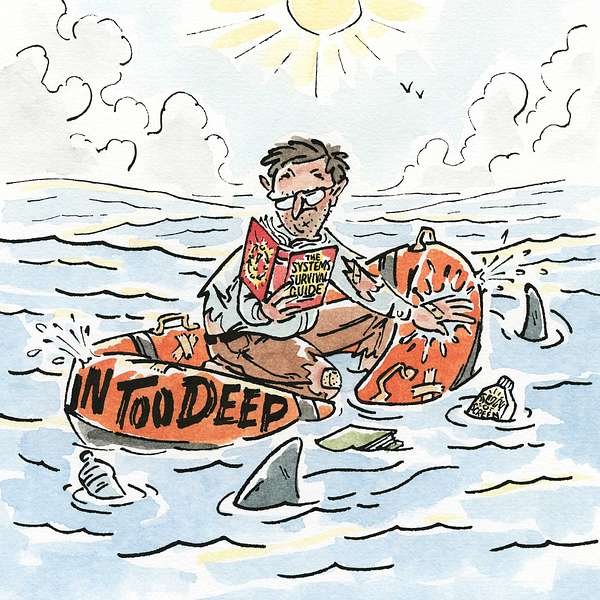

In Too Deep

We explore how changemakers across the globe are engaging complexity to tackle tough issues. Created by the team at Kumu.io

In Too Deep

The way of the forest: Supporting ecosystems with a nature-inspired lens | Episode 13

In this episode we’re joined by Santiago Bunce, founder of Via Bosque, a company that helps clients achieve transformative change by integrating leadership tools with nature-inspired principles. Santiago shares his unique perspective on building ecosystems and how it can be applied across different contexts to create positive, lasting change.

Tune in for a deep dive into:

- Designing ecosystems through a nature-inspired lens

- Approaching systems thinking in different cultural contexts

- Evolving from "good vs bad" to a mindset of "good, better, best"

If you're passionate about sustainability, innovation, and the interconnectedness of our world, this episode is for you. Subscribe to the In Too Deep Podcast to stay updated on future episodes of meaningful conversations about tackling tough problems.

J: You probably know our mission at KUMU is to build tools to tackle tough problems. So, by way of introduction, I’d love for you to share a bit about your background, and also, when you think about tough problems, what are some of the though problems you encounter or try to solve in your work?

S: Yeah, hot out of the gate! I’m Santiago Bunce. I lead an organization called ViaBosque, which translates to ‘Way of the Forest’ from Spanish. We incorporate biomimicry from the natural world into our approach to leadership and coalition building. Our services include executive coaching, facilitation analysis, communication strategies, and comprehensive plans to help teams and networks collaborate effectively.

I was introduced to network theory early in my career. One of my first jobs after school was with the Interaction Institute for Social Change, based in Boston. They focused on facilitation and what they called ‘multi-stakeholder involvement’ at the time. I learned that networks are not only a concept but also have a science behind them, and there is an intentional way to develop and weave them. This sparked my growing interest in the field.

Then I came across Kumu a few years ago, which has been an invaluable tool for helping us think through some of these big challenges. We work extensively in areas like affordable housing, economic development, progressive tax systems in the United States, and renewable energy. These are all adaptive challenges, where solutions are not simply ‘right’ or ‘wrong’, but can be ‘good’, ‘better’, or ‘best’. We take a systems approach to these issues as much as we can, recognizing how interconnected they are — for example, taxes impact climate, housing affects economic development, and so on. This interconnectedness is a central aspect of all our work.

J: Got it. You mentioned biomimicry as part of the firm’s approach, and I’ve also noticed you use the term ‘nature-inspired lens.’ Could you elaborate on what that looks like in practice? Additionally, has this perspective always been part of your life, or how did you come to ensure it remains a central focus?

S: No, it wasn’t always part of my life. I’ve always appreciated nature and had an interest in meteorology, but it wasn’t until about ten years ago that I learned about biomimicry. It struck me as a fascinating and unique approach to designing products, at the time.

Then, around five years ago, I began exploring how biomimicry could influence how people interact within organizations, both formal and informal. I discovered that many animals and plants have complex relationships, offering valuable lessons we can apply to our work. Our focus is mostly on teams and coalitions, primarily in the nonprofit sector, though we also engage in corporate responsibility and social impact initiatives.

We now use a three-part framework: Performance, Emergence, and Ecosystems:

- Performance covers traditional aspects of leadership development, such as goal setting, strategy, team management, and influencing others in meaningful ways, rather than through transactional interactions. Here we draw inspiration from fauna, examining how animals strategize, set goals and interact together.

- Emergence focuses on creating conditions for new ideas and new voices to be heard. In this section we mainly look at plants and fungi to understand the catalysts and conditions necessary for growth and innovation.

- Ecosystems explore how different elements coexist, using examples from wetlands, forests, and coral reefs as reference points.

We integrate this with our work in Kumu and systems thinking, mapping and weaving networks, and identifying leverage points. This approach is not only effective but also serves as a homage to the natural world, which I deeply value and hope to preserve for future generations, including my own children.

J: Let’s focus on those three areas a bit more, because they offer a powerful perspective. The elements you mentioned in Performance, like strategy and goal setting, are often not considered alongside Emergence, and vice versa. When people emphasize Emergence, they sometimes overlook the structured aspects of Performance. Can you elaborate on how these elements interact? Do they play in tension with each other, or how do they show up differently, especially since you prioritize Emergence and Ecosystems?

Also, could you expand on your concept of leadership? How does your approach differ from traditional views of leadership?

S: I’ve been fortunate to serve as an executive coach in a program connected to affordable housing for the past few years. The program is powerful for many reasons, particularly the tools and disciplines it teaches leaders. While these tools aren’t necessarily new or innovative, they often provide language for concepts that leaders were already intuitively practicing or had learned differently.

There seems to be a body of study and practice in leadership focused on traditional elements — like what leadership looks like in an ideal environment, how to set SMART goals, and how to prioritize based on cost, people power, or the organization’s vision. However, it felt to me that something was missing: what does leadership look like when things don’t flow smoothly?

Though leadership has traditionally addressed these issues a fair bit, a significant focus in the last few decades has been on creating safe spaces for new ideas and new voices to emerge. For example, as a white-presenting Latino male, I have a lot of agency in rooms, which isn’t the case for everyone, particularly women and people of color. Elevating these voices doesn’t happen organically; it requires intentional effort.

There’s now a growing emphasis on incorporating elements like psychological safety, curiosity, addressing biases, and breaking out of echo chambers to avoid confirmation bias. These components are being integrated into the leadership program I mentioned, not just because of our work, but also because times are changing. Performance and Emergence must work together — creating space for new voices while clearly managing and aligning with collective goals. This is where, I think, the ecosystem concept fits in, as it mirrors the natural balance and interaction of different elements in an ecosystem, ensuring they coexist and function effectively. So I do think that Performance and Emergence go together, because you can’t create space for new voices without also managing and being clear about where you want to go together.

J: Got it. You often use the language of ‘ecosystems’, which I find interesting. When people come to us at Kumu asking to ‘map their ecosystem,’ the reality is that what that means can be pretty unique in each case.

Can you elaborate on how you define an ecosystem, and what it looks like practically when you’re supporting people in building ecosystems around their work? Whether it’s in the nonprofit or philanthropic space, or on the corporate side, what does that process look like?

S: Absolutely. We encounter the same issue — ‘ecosystem’ has become a bit of a buzzword, and everyone has their own interpretation of it. So, we looked at natural ecosystems to identify their key characteristics and see how we could apply them in a business context. For us, this is how we try to define an ecosystem, as having these elements:

- Boundaries: An ecosystem typically has a defined boundary, which can include transition zones, whether geographic, demographic, or otherwise.

- Conditions: These are the broader, deeper factors at play, such as policies or economic conditions.

- Actors and Relationships: The individuals or organizations involved, and the relationships between them.

- Goals and Results: The objectives the ecosystem is working toward, and the outcomes it aims to achieve.

These are the key characteristics we use when thinking about ecosystem building and mapping. We’ll work with a group to map these elements and understand how they interact.

Recently, we worked on a project in South Florida focused on small business development. The goal was to reframe and reorient the small business ecosystem in the region. The first question we had to address was, ‘Who are we talking about?’ South Florida spans from Miami-Dade County to Palm Beach County, and includes the City of Miami and even the Keys, with varying demographics.

This project was specifically focused on small businesses, with an added emphasis on climate resilience. Defining these boundaries helps clarify what’s included and what’s not, which is crucial for managing expectations. Much of this work revolves around setting clear expectations, speaking the same language, and ensuring everyone is aligned — even if not everyone is headed in exactly the same direction.

Find the Kumu presentation that resulted from this project here.

When it comes to the goals and results within an ecosystem, the question I find interesting is whether we look at goals for individual entities — like animals or species — or at a broader ecosystem level. What kind of mindset shift happens when we approach goals from these two perspectives? How do we hold goals and results differently in this context?

From the perspective of an individual animal or plant, the goal is typically survival and reproduction — whatever that looks like for that species. For the ecosystem, the goal is to create the conditions that support those individual entities, which requires some level of equilibrium.

Both natural and organizational ecosystems experience shocks and stressors. Stressors being long-term, chronic issues that negatively impact the overall space, like a recession or an industry facing fluctuating philanthropic donations. While shocks, on the other hand, are one-off events with powerful impacts, like a new infusion of capital or the emergence of a new competitor, such as the impact of AI on industries.

The goals in this context differ, but the ecosystem itself must set the conditions where smaller entities — whether teams, individual leaders, or organizations — can thrive, however they define thriving, using their own metrics.

J: Got it. I know you do a fair amount of network mapping, particularly in the context of building ecosystems. How do you approach that process? I’m assuming you don’t create a network map for every client, so when do you decide it’s worth doing? What does the process look like, and how do you set expectations around it?

Finally, do you have any best practices or advice for others who might be considering network mapping in similar contexts?

S: One of the fortunate things about many of the organizations we work with is their genuine interest in relationships. They understand that complex challenges require more than one solver. You’ve probably heard this before — or maybe even said it yourself. It’s not just that there’s often more than one solution that can work simultaneously; it’s also that no single entity can solve these challenges alone. We’ve been lucky that many of the organizations we collaborate with already share this mindset.

They understand it’s going to take collaboration. And whenever we talk about network mapping or show an example of a past map, the reaction is often, “Oh, wow, that’s really cool,” even if they don’t fully grasp all the details. From there, we explain that these relationships already exist, but they’re typically only visible to the parties involved. The question becomes: how do we broaden that understanding to a larger group?

We start from a place of curiosity — asking, “What does this mean?” I’ve also seen in your work, Jeff, that just because someone appears peripheral in a network doesn’t mean it was designed that way. It could simply be a choice. Helping people explore those dynamics and ask those kinds of questions is often a valuable exercise in itself.

Beyond that, while these connections often happen organically, there are also intentional ways to engage the group in weaving those relationships. That’s where things get really exciting.

We’ve found that organizations eager to build relationships, recognize the importance of coalitions, and understand how achieving broader goals can make their own work easier are typically the most aligned and interested in mapping efforts. We also see interest from organizations that want to identify key players — whether it’s for policy-related initiatives, alumni networks, or understanding who holds space or trust within the network. Those are the groups we tend to work with.

But, it’s also important to set expectations — network mapping isn’t going to solve everything. In fact, it often raises more questions at the start. And if you want to see meaningful changes in the network, it takes time and consistent effort.

J: When people are doing network mapping, how often do they go down to the level of collecting individual relationship data? For example, asking questions like, “Who are the top five people you’re strongly connected to?” or “Who are you actively collaborating with?” These maps show the person-to-person relational web.

On the other hand, some maps are more conceptual — focused on connections through shared projects or similar organizations. Do you tend to lean toward one approach over the other? If it’s a blend, what helps you decide which approach is the right fit for a given context?

S: I think it’s a bit of a blend. The bounded network mapping we do is typically for entities with established memberships that haven’t really explored this before. They want to understand who’s connected within their network, how they can be better stewards of those connections, and how they can convene the network more effectively.

On the other hand, when we work in public health or with organizational coalitions, it’s often more unbounded and egocentric — focusing on identifying who else should be on their radar as part of the broader network.

It’s been a nice mix, and we don’t necessarily favor one approach over the other. That said, for member-based groups — whether organizations or individuals — we tend to start with a bounded approach as a baseline for the first round.

J: How much of your work focuses on the strategy side? Does it often shift into creating systems maps, like causal loop diagrams? And if you do work on those, what processes have you found to be most effective for building them out?

S: I’d say only about 20% of our mapping-related work gets into systems thinking and causal loop diagrams. Part of the reason is that creating a good systems map often requires more than a one-off meeting. It’s more beneficial to have an arc of work over time so people can revisit and refine it.

Another challenge is that many of us are still tied to linear thinking. Shifting to systems thinking and mapping—whether it’s done analog or digitally—takes some adjustment. That said, we do promote it and offer trainings, and the folks who engage in it really enjoy the process. It often provides valuable insights about where to focus attention.

For example, a few months ago, we worked with a finance nonprofit on a systems thinking exercise. They split into three groups and did the activity on paper. It was incredibly productive. They gained a clearer understanding of how interconnected the moving parts were, especially when they’d previously been focused on just one aspect. There was even overlap across groups in identifying potential leverage points and distinguishing what they could control versus what they’d simply have to respond to.

J: I agree with you — there’s definitely an element of unlearning and relearning involved. I also wonder how much of a breakthrough could come from incorporating more accessible metaphors, especially around ecosystems. If we could find ways to make those metaphors easier to understand, it might create a smoother entry point, compared to the complexity that people often associate with systems mapping. Sometimes, I feel like we’re our own worst enemy in that regard.

S: Yeah, I really struggle with that too. I’ve been told I speak too technical at times, so it’s something I’ve been working on for years. But the nature metaphors are really powerful because there are parts of nature we all recognize, whether or not we’ve spent a lot of time in a forest or near a coral reef. The relationships within nature are familiar to us.

Then, when you start talking about ecosystem engineers — keystone animals that have a disproportionate impact on larger systems — it’s a great way to explain leverage points. You can relate that back to how a specific part of the system, like an ecosystem engineer, influences the whole system. For us, the beaver often comes up as an example — it’s a great illustration of that dynamic.

J: Another thing that comes up a lot for us at Kumu is the power of narratives — especially through storytelling. We focus on using visuals to make the story engaging, but in the context of systems work and networks, it’s also about capturing people’s narratives. How do we gather those stories and share them in ways that help others see the system in a new light?

How does this come up for you? Have you found effective ways to capture and share narratives in compelling ways?

S: In our work, much of the narrative sharing and exploration of meaning typically happens during facilitated conversations. I’m not sure we’re currently tracking those narratives in a way that’s captured directly in the maps. There’s a tool called Cognitive Edge — have you heard of it? They have this SenseMaker tool.

We’ve worked with some groups that use SenseMaker, and we’ve integrated it into parts of the qualitative analysis. For example, when providing recommendations or prompts for groups to explore the maps, we might look at the stories captured in SenseMaker and highlight trends that seem to align with certain patterns in the map or clusters. We do this without overly anchoring the discussion, but it’s a way to connect the stories to the network visualizations.

I think this is an area where we could continue to learn and explore more

J: One question I have is about your background. You’ve been in and out of various cultural contexts, and where you live is also a dynamic environment. So, I’m curious to hear your lessons learned. Where have you seen very different definitions of terms or misunderstandings of concepts?

Given that ecosystem work often spans multiple cultures and geographies, how do we approach this work successfully? What do we need to be especially sensitive to as we navigate these diverse contexts?

S: I’m really enjoying these questions, Jeff. From a cultural context perspective, I mentioned agency earlier, and I’ve noticed a few things. For example, in the U.S., compared to Latin America, where we’ve done some work, there’s generally more agency spread across organizations or teams in the U.S. This allows for a bit more pushback and curiosity. It’s not perfect, of course, but it creates space for more engagement and critical thinking.

In some organizations in Latin America, though, that level of agency has been a bit lacking, which makes it harder to foster that kind of dynamic engagement. In these contexts, I feel like the systems thinking muscle isn’t as developed.

The flip side seems to be true when comparing Europe and the U.S., at least in terms of systems thinking. I’ve noticed — and I’d be curious about your perspective on this too — that the science of network mapping and social networks is a bit more developed and explored in Europe. We’ve seen this with the clients we’ve worked with there, compared to the U.S. It’s not to say that the U.S. can’t catch up, but there’s definitely a difference in the level of maturity.

And with Latin American clients, it’s not that agency can’t be developed — it definitely can. But just looking at the comparisons, those are some of the things we’ve observed. So what does that mean? When working with clients in Latin America, we make sure to set clear expectations, especially with leadership, about what we aim to achieve and why it’s important for the conversations.

Some of this is cultural, so we can’t push against it too much. We try to be respectful and competent in understanding those cultural differences, but a big part of the work is setting expectations — what’s possible, what’s in bounds, and what’s out of bounds within the work we’re doing together.

When comparing Europe to the U.S., in terms of systems mapping and systems thinking, we tend to do a bit more didactic training with our U.S. clients than we do with European ones. Again, I’m speaking broadly and don’t mean to be unfair to any specific group, but these are just some general observations.

J: I also wonder sometimes about the U.S. and its history of rugged individualism, right? There’s this narrative of doing it alone, which contrasts with some countries on other continents where there’s a stronger sense of the importance of society, collectives, and the whole system. That difference has significant implications for how people understand networks and their value, especially compared to more hierarchical thinking.

New Zealand is another interesting case. Early on, when we looked at a geographic map of Kumu users, we noticed a surprising number from New Zealand. We wondered, “What’s going on down there?” But it’s really about values. There’s a cultural and community orientation in New Zealand that aligns well with systems thinking and network-oriented perspectives. It’s just a different way of viewing and interacting with the world.

S: Are you familiar with Father Richard Rohr? He’s a priest and author who has written several books. He also founded a center in New Mexico called the Center for Contemplation and Action. One of his books, The Naked Now, explores the challenge in Western thought of living within dualities. In the book, he discusses how Western culture tends to view things in opposites — ‘good’ versus ‘bad’, ‘correct’ versus ‘incorrect’ — whereas Eastern cultures are more comfortable with the space in between, embracing a flow of ‘good’, ‘better’, and ‘best’.

This idea of duality in Western thought is what I think informs the framework of “good, better, best” versus “correct and incorrect.” Rohr points out that Western societies often struggle to exist in that middle ground ‘grey space’, while Eastern cultures seem more accustomed to it. Interestingly, I’ve noticed that organizations in places like Australia and New Zealand are more open to these ideas, as are some European countries, possibly due to their historical engagement with Eastern philosophies and complexity thinking.

In this framework, the maps of reality are never clean or straightforward. There are multiple perspectives, and while you gain more clarity, it also leads to more questions. The goal isn’t necessarily to find the “right” answer, but rather to explore the possibilities.

J: Can you walk us through a practical example of how you approach the “good, better, best” framework? Specifically, how are you applying this in your coaching with clients or communities? How do you help them hold this perspective differently? Does it relate to strategy or decision-making, or is it something else? I’d love for you to share how you bring this concept to life in real-world scenarios.

S: Yeah, absolutely. When we think about the “good, better, best” framework, it’s really about helping people let go of preconceived expectations, especially leaders who might have a specific idea of how a project should unfold or what the final outcome should look like.

We often work with organizations that focus on community engagement — connecting with the residents or community members they serve, regardless of the industry. There isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach to community engagement. For example, you could use a digital strategy, a door-to-door approach, or a town hall format where a lot of people gather in one space. All of these strategies can have some level of success, but some are better than others depending on the context.

For instance, if you’re working with older adults who aren’t digitally literate, a digital strategy might be good, but it’s not the best approach. A community center meeting could be a better option in that case. The goal is to help people think through these options and consider what might work best in a given situation.

One framework that I find helpful, from the Interaction Institute, involves thinking about a triangle of process, results, and relationships. Often, people are oriented toward one of these three aspects — some focus on results, while others are more concerned with process (like how long a document is, for example). These elements don’t have to be mutually exclusive, but they do highlight where people are coming from.

If we can approach things from this lens — considering good, better, and best in terms of both results and processes — then it becomes easier to let go of rigid expectations and be more open to finding the most effective approach.

J: Shifting gears a bit more directly to Kumu, I know you’ve spent a fair amount of time mapping and experimenting within the platform. When you think about the future, what are your hopes for it? What features or possibilities do you wish were already available, or might be possible down the line? What are some of your aspirations for where Kumu could go, whether it stays the same or evolves in a different direction?

S: I always tell anyone connected to Kumu that you all are fantastic, and I’m so grateful for what you’ve created — both when it was first launched and how it continues to evolve. It’s been incredible, so congratulations, and thank you. A couple of weeks ago, I mentioned to one of your colleagues that it would be great to have a feature that allows you to overlay a network map with a systems map.

I’m not sure what the technical solution would look like, but here’s the idea: it would be amazing if I could, say, double-click on a loop or an element of a systems map and see which players are connected to that part of the system. For example, if we’re working on projects related to climate resilience, affordable housing, and economic development, there are organizations focused on each of those areas. You could build a systems map that connects all of those issues, but it would be really powerful to also visualize the organizations and the relationships between them — perhaps even showing the clusters tied to each specific issue.

J: I hear you, and I agree. It’s an area where there’s a lot of intuition about how systems and networks can overlap. A big part of starting Kumu was realizing that insight. We initially focused solely on relationship mapping and visualizing networks, then brought in the systems mapping soon after because we kept seeing that people were using separate tools for these, which didn’t make sense. These things are closely related, yet people were still struggling to connect them.

Part of it is the limitations of Kumu, but it’s also a complex challenge on its own. For instance, we’ve seen people create maps manually by drawing systems maps, with stakeholders or organizations surrounding the map and manually connecting them with lines to show the relationships or feedback loops they influence. It’s a valid approach, but it’s very manual.

There are ways we could improve or unlock this, but to me, it still feels like a bit of the “Holy Grail” — finding a clean, thoughtful way to do this seamlessly, because the insights that come from that would be incredibly powerful.

Another dream I have for the future is exploring ways to access profiles more like a survey. Imagine giving someone a URL to their profile, where they can only access their own information. From there, they could fill out details about who they’re connected to, their background, and so on. That could be a really cool development, and I’d love to see something like that in the future.

S: Yeah, that’s really appealing. What I also really value, and my assumption is that this is tied to people who are naturally interested in networks, is the culture I see in the community. For example, Christine [Capra]and I had a great conversation, and the discussion with you and June [Holley] was super helpful. It’s clear that the people in this space really embody a mindset that a mentor of mine shared with me years ago. His name was John Gibran Rivera, and he introduced me to the phrase “low ego, high impact.” I really feel like that embodies the Kumu community and the broader systems thinking community. It’s a quality I deeply appreciate, and I’m grateful for it because I’ve learned so much from people who live this out.

J: Yeah, I think that’s something really special. We’ve honestly felt really lucky with the organic growth path Kumu has taken, and we’ve found a truly unique community of people. So, in that way, we feel really blessed.

To wrap up, I think there are two parts to this. You can start wherever you’d like. One is about inspiration and hope — especially in the current context, which is interesting right now. What gives you hope? What are some of the sources you turn to for inspiration?

And the second part — are there any particular values you’d emphasize that feel important for us to hold more prominently as we move forward with this work? What should we focus on as we think about doing this work well and planning the next steps?

S: One of the things I love about my job is that I get to work with people across the country who are leading really meaningful and impactful work. That brings me a lot of hope — seeing others do what they love and contribute in ways that matter. In my role at ViaBosque, I’m an executive coach, and I have the opportunity to engage with people in ways they might not often get to with their colleagues, for various reasons. There’s so much wisdom, hope, and motivation in those conversations, and it’s inspiring to witness and be a part of. Personally, that gives me a lot of hope and peace on a broader scale.

I studied Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and Judaism in undergrad (Comparative Theology), and I read a really insightful book on Buddhist social teaching. There’s a story shared in many traditions that sticks with me: After something like 9/11, a teenager is upset and angry, particularly towards the Arab community. The teen goes to his grandfather and says, “I’m so angry.” The grandfather replies, “I’m angry too, but there are two wolves in your heart — one filled with love and the other with hate. They’re fighting.” The teen asks, “Well, which one will win?” The grandfather answers, “Whichever one you feed.”

I think it’s easy to be cynical and pessimistic, especially when there’s no shortage of reasons to worry. But I also believe there’s just as much, if not more, to be hopeful for. We still want good things. We still want to care for one another, for the planet, and for future generations. If we feed those hopes, they will win.

J: That’s wonderful. I think it’s really hopeful — whether it’s about our shared humanity or the potential of nature-based solutions. As you mentioned, it’s interesting how people are often so focused on our interconnections with each other, yet forget the deep connection to the natural world and everything beyond us. Maybe we can use that focus on human connections as a bridge to expand how we think about our relationship with nature.

But absolutely. Fingers crossed — we can get there. I think the broader trends are moving in the right direction, even though there may be some short-term fluctuations that make things a little trickier.

S: Absolutely. And it helps to spend time in in nature to keep that connection top of mind. And if we can’t physically be in nature, at least we can talk about it. Maybe that will get people outside, too.