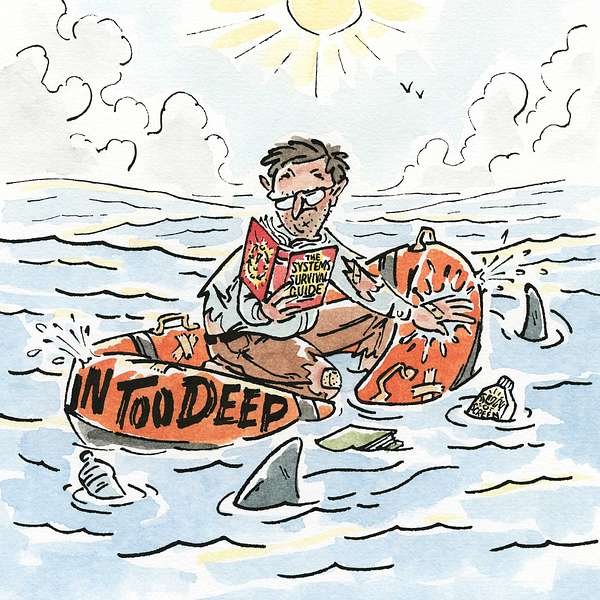

In Too Deep

We explore how changemakers across the globe are engaging complexity to tackle tough issues. Created by the team at Kumu.io

In Too Deep

Creating a future where nature and people can thrive together | Episode 4

Josh Goldstein is a Director of the Bridge Collaborative at The Nature Conservancy, where he works to bring about fundamental changes about how we think, plan and fund work across the environment, health and development communities. Josh's work pushes against the dominant paradigm that we can either support economic development OR protect the environment, and instead looks at how The Nature Conservancy's work can benefit both nature and people.

Too often we have a dominant paradigm that we either can on the one hand, support economic development and improve people's lives, OR we can protect the environment. Then it's only as nations get wealthier or people get wealthier that they start to care about the environment.

Jeff:Welcome to In Too Deep, the place for meaningful conversations about tackling tough problems. This week we're rejoined by Sam Rye and also Josh Goldstein, who is a director of the Bridge Collaborative at The Nature Conservancy. Josh has a fascinating role really working to bring about some fundamental changes in how we think, plan, and fund work across the environment, health, and development communities and is really confronting some of the tradeoffs we've taken as given head on. Enjoy.

Sam:I was wondering to start with whether you could tell me a little bit about The Nature Conservancy and what you're doing there.

Josh:Sure. I've been five years at The Nature Conservancy and we are a global conservation organization. We work in over 70 countries around the world and we do all kinds of conservation work, really with an eye towards how we create a future where nature and people thrive together. And it's a mission and a vision that I love and really inspires my work. I personally am part of the global science team, which is a group that supports the work of the conservancy in all the places that we work around the globe.

Sam:Wonderful. I was wondering if you could tell me a little bit about your background, how you got started with systems practice and how that sort of led you into the work you're doing now?

Josh:Sure. I feel like I stumbled into systems practice unintentionally, but I've come to really love it and feel and recognize its importance. So I was, you know, if I wind the clock back to thinking about growing up and thinking about even college, I was in a much more traditional approach of looking at individual disciplines or you know, more sort of focused entry points to learning. When I was preparing for Grad School, I started to have a real interest in understanding how, you know, the basic science connects to our, our cultures, our economic systems and many other social factors. And that really led me to what was a fantastic program at Stanford University. I was part of the first cohort of what's called the interdisciplinary program in environment and resources, a program that back at the time was quite unique, and allowing students to enter in and really purposely do interdisciplinary research. And the work that I did there was around combining ecology and economics and looking at some questions around how we value the benefits nature provides to people and also how we think about questions around maximizing return on investment from conservation investments, again to benefit nature and people. So from there I went on to become a professor of ecological economics at Colorado State University and enjoyed that position very much, but then had a really neat opportunity to shift gears and go to The Nature Conservancy and start to really get excited about doing science much closer to the action of conservation work on the ground and to support the strategy of our organization. And it's been just a fantastic five years.

Sam:Wonderful. Before we started you were telling me a little bit about some of the work you were doing with that strategy and the mission. I think it's a really important place to talk about. Could you tell me a little bit about that, that work and potentially how you used a little bit of systems practice to reshape that mission?

Josh:Yeah, so in 2015, The Nature Conservancy adopted a new vision statement, which for the first time explicitly stated how we believe it's important to do our conservation work to benefit nature and people and really seeing that as a way that nature and people can thrive together. I think too often we have a dominant paradigm, which I actually think comes from a lack of a systems understanding of challenges that we either can on the one hand, you know, support economic development and progress from an economic perspective and improve people's lives, or you know, the tradeoff mentality, or we can protect the environment. Then it's only as nations get wealthier or people get wealthier that they start to care about the environment. I think we now have decades of understanding that that's really not the case and that narrative of, you know, jobs versus the environment or economy versus the environment is a false choice. And, I think the systems view really turns it on its head to understand how intricately connected the environment and nature is, as input and the foundation for the economy and for society, but also how, if we're going to solve food, food insecurity and energy insecurity and water insecurity and all these global challenges, that needs to go hand in hand with solving environmental challenges. And so the work that we did which really got us into some systems practice at The Nature Conservancy was all around asking a pretty simple question that took a lot of effort to, to address. That was really fun work. Basically it's saying, you know, if we're serious about a future in which nature and people thrive, what are the big challenges that need to be addressed? How are the big problems that cause biodiversity loss around the world from habitat conversion and degradation to invasive species to pollution and so on, how are they connected to the major challenges facing human wellbeing? And so we created a giant map that in Kumu backed by all kinds of evidence from all kinds of sectors to allow us to answer this question. You'll be able to elevate out a set of key questions, key challenges that linked the fate of nature and people going forward. And that work, we can get more into that, so that work has led to the role that I'm in currently at The Nature Conservancy, which is, as the director of the bridge collaborative. And the bridge collaborative is a partnership of The Nature Conservancy with partners in the global health and development sectors with Path, a global health organization out of Seattle, the International Food Policy Research Institute and Duke University as an academic partner. And our work together is to really accelerate a paradigm shift in action towards solving these tightly connected health development and environment challenges. Everything from aligning evidence better across these sectors, which is often not done to building skills and networks, to go back to training. Many of us are trained in much more siloed ways. How can we bring those sectors together. And then really driving more alignment of agendas and action across, you know, leading organizations and funders so that we actually are prepared to solve these challenges at the most important global level possible.

Sam:That's wonderful. I really sort of hear how the systems thinking and the systems mindset has become kind of culturally based in TNC and that bridge collaborative partnership now. I would love to hear a little bit about the edge of your learning in regards to that policy shift and other initiatives that you've been working on at the moment. Um, yeah, I'd love to hear some of maybe how systems practices are being used in that partnership and how it's being used maybe at a strategy level, but maybe also a tactical level.

Josh:Yeah. So as we scope projects and we do our work, I think we're always seeing the system connections that are out there. And yeah, we're often hearing a real range of perspectives from the folks we engaged whether they are researchers or practitioners doing work in communities, whether they're leaders of organizations or funders. And so recognizing that there's still a lot of work to make the case that integrated solutions, those that come from real systems perspective are going to be more efficient and cost effective in terms of solving problems. And so we really are working to build better evidence and support for that hypothesis which we think is a really solid one. And I'd say most people are really sort of get the system connections so we can really start to understand how the things that the global health community is trying to solve and some of the biggest problems, you know, the leading cause of death and disease around the world, they're all tied back to food and diet related factors. So malnutrition and also poor diets and those things are tied so tightly to agriculture being one of the strongest drivers of biodiversity loss around the world and all the major challenges around food and nutrition security with the 800 million people who are still hungry in the world and different estimates, but your many billions who are malnourished both poor nutrition because they're under nourished and also on the overweight and obesity side. And so you have all these kind of really tight connections that are increasingly documented and I think our agile learning is in part to help further build out the understanding of how the connections manifest themselves in places around the world. I can give some examples that later if you'd like, but even more so the so what? So what do we do about that? How do we take this system's understanding so we can build out all these connections and that's a really powerful way we find to bring people together who have not, not worked across theses sectors and understand each other. And you know, the process of building out a systems diagram really facilitates communication. It builds some understanding and trust amongst the group. Then you're sort of left with, um, you know, a big exploding diagram. How do you then look at that and be smart about how you understand the system connections, but understand a smart slice through them to be able to actually drive action. And to me, that's the most important thing about a systems perspective is if we're going to act and solve problems, we'd better know the connections from a bigger systems view because then it's going to empower us to be smart about our targeted actions and how to use our resources most effectively.

Sam:Maybe let's dig into that a little bit about how you're currently doing that work. How are you transitioning from the big systems view into the smart slices as you put it and how you generate action from that point?

Josh:Yeah. So I'll give you an example of a project that we're working to get underway, which for me has stitched together some pieces that are quite surprising to me and I'll just admit to you, perhaps smarter people than me would know these connections, but they've been really fascinating to me. So here in the US, as in some other parts of the world, there's a real devastating opioid addiction crisis. And that is affecting rural communities in many communities around the country in really profound ways in just a short amount of time it's really risen to one of the top health challenges here in the US. That is connected in a way I never would have guessed to some work that we're trying to advance through The Nature Conservancy with the support of bridge collaborative around looking at a post-coal economy in central Appalachians in West Virginia in that region. And really looking at how there's a lot of exciting thinking around how can we transition away from coal, in support of, you know, while also delivering opportunity, economic opportunity and retraining for those rural communities who've had economies based on coal for some time, and looking at a green economy based on sustainable timber, on solar, or other renewable energy and also potentially ecotourism. And it's a great idea and a great opportunity. It's actually coming head on with the opioid crisis in a way that I never would have guessed. And this is where we're seeing that the opioid addiction is actually really devastating the workforce and communities in these areas. And so can we actually take these two problems which sit side by side from a more narrow view, and when you start to step back and really build out the systems understanding of what's going on in these regions, you recognize that they're really tightly connected in important ways. And so can we take that understanding of the problem and actually look towards solutions that a systems view empowers where we can partner workforce training with an opioid addiction treatment program that's part of the workforce training as an avenue to help prepare and empower a workforce that is ready to deliver the green economy. And so either one on its own, you know, without an economic future, there's a lot of challenges in the health side. You won't be able to create that economic transition unless you start to address the major health and other community issues there. So for me it sort of takes a narrative which is really challenging on the, on the health side in the US, and actually provides you a positive view of what can be done. So we're just getting into this work with fantastic partners and I think it's really exciting and the kind of systems direction that we're trying to head in.

Sam:Wonderful that sounds like a really exciting project. I wonder if we can dig in even a little bit further into how those sorts of programs, projects, initiatives sort of come about and how, I guess one of my, one of my interests is about the dynamics of complexity and, and sort of how that overlays with systems thinking, and so complexity sort of stating that things are emergent and we can't actually plan our way into the future, changes come in nonlinear. How, how are you using these sorts of systems insights, knowing what you know about complexity, to sort of work more, I don't know what the current words are agile or experimentally with those kinds of projects that you're creating.

Josh:Yeah, so I think one common comment we get when we do this kind of systems work with teams is, you've just taken something that I already thought was complex and you've just made it way more complex. Oh my God, what do we do with this? Right? Almost like a, yeah, I understand things better, but I almost feel paralyzed by the level of complexity that you've built out. And so I think what we really try to do is uh, it was mentioned earlier is, I think if you just build out an understanding of the system and sort of stop there, then it really does lead to paralysis and sort of I don't know what to do. And so you really need to sort of make sure that you go into this work, understanding what you're trying to get out of it, which is often for our work informing strategy and then how to understand where there's the smartest entry points where you can get at the outcomes you're looking for. And so, um, I think, you know, some things that we do through our work and that we'll see if these sort of make sense. One thing we actually try to do is a lot of rapid iterative conversations and colliding or cross pollinating expertise that often does not interact with each other. So, and we actually, someone once commented that one of their takeaways from working with us is it seems like we only like to do things fast. You know, and um, you know, I sort of laughed because I think there's actually some value in pushing people not overlay fast and thinking and building out your systems understanding, but a bit uncomfortable, you know, a bit faster than you want to go so you don't get stuck and you can keep moving those iterative ways. So what we do often is host cross sector workshops and we use tools from human centered design or you know lean innovation work to help guide us. And we're definitely early on our learning curve on those kinds of methods, but we've seen a lot of value in them. So I'll tell a story about from actually a training we had by a group called smallify back about a year ago. And they were training us in these sort of design innovation methods and out of a two day training with, four people who had basically not interacted much, two of them had but most of them had not interacted in real ways before. They used this kind of systems approach and these design innovation methods to develop a whole new idea for how you can really accelerate integration of environmental considerations into refugee and humanitarian assistance with camp planning around the world. And we've tested it now in Bangladesh in really the first prototype of that. But, um, you know, we really entered into that meeting thinking about, you know, this idea that, gosh, there's so many important dimensions around humanitarian assistance as, as displacement goes from, you know, what used to be decades ago, a truly short term crisis to now being five, 10, even 20 plus years in some cases. And so the considerations around environment and around really sustained planning beyond the basics of food, water and shelter become critical. And so we did. We basically used these methods of, you know, lots of rapid ideation, rapid prototyping, and building out ideas. And we came out of this with an idea called refugee action for people and planet or RAPP labs. And it's basically the idea of how you can crowdsource in expertise from key sectors, key perspectives, you know, really close to the field when key decisions are being made so that you have that knowledge ready to move. And so we, I think what we try to do is really balance, you know, and understand and building out complexity, but always in honing in on decision opportunities. And for us, that really creates a good balance. If there's a decision that's coming and there's always decisions, but you know, one where there's a good opportunity to influence it in a good way. We think, you know, these fast processes to build out understanding can really be helpful. And then focusing on the so-what of what, what can we do to make that decision a better one than it would have been before? And that's a powerful lens.

Sam:Excellent. It sounds like that spinning of fast thinking, makes me really think about the importance, I think it was Daniel Kahneman that write the fast thinking, slow thinking book. So I'm interested in that sort of how do we twin that fast thinking, these processes those rapid iterations, those prototypes, how do we twin that with the slower thinking basically that actually spots patterns and enables us to see deeper trends at play. So I'm interested in that way. Are you connecting the fast thinking with the sort of systems mapping piece that you did, like a living document that keeps changing as you generate new insights with those fast thinking, iterative cycles? Is that something you're planning to do with the new projects?

Josh:Yeah, I mean if I, I might go back to the major project we've done in Kumu which is around this global situation analysis, looking at how the major global drivers of biodiversity loss are connected through causal pathways and shared root causes to the big challenges for human wellbeing. And we use that in a really neat way where we were building out, you know, we sort of create our own first prototype based on reading a whole wide range of literature and, you know, recognizing that sometimes the best first step is to read a bunch and process in a slower way, but then get something out that people can react to. Because, you know, every model is wrong some are useful. That's true of system maps and, um, and it also becomes a tool to get feedback but also to facilitate the conversation. And so we, we use that map, you know, the version we have now is relatively stable I'd say, but I can't even guess at how many versions we went through even before Kumu there's probably 10 or 15 versions in powerpoint which was incredibly clunky. But you know, it's fantastic to be able to get a tool where we could really interact in facilitated conversation and show people are basically use it to illustrate our thinking. And then for them to get feedback in really tangible ways. That I think is an example of the sort of fast and slow where there are periods where you're really trying to patiently, you incorporate feedback and thinking about what it means and thinking about the best way to represent the system and then there's, I think times you've really just got to lean in and get in a ton of feedback and really get people actively talking about it, knowing that not every everything can be addressed or every piece of feedback is perfectly spot on, but it really spurs that conversation about, you know, about what are we trying to get at here and are we representing it in a way that has shared understanding and can drive shared action.

Sam:Yeah that's wonderful, it's certainly something I grappled with during my masters. Having just finished that up I found that having generated the kind of a systems map or a few of the systems story as I was calling it, I found there were so many stories within that story. So kinda of working out which ones you surface, how you, how you present them, I really loved Kumu's presentation tool for that. Um, but yeah, as you say, how you then integrate more feedback, how you, how you invite participation and use it as a provocation rather than a source of truth. It's a really great perspective. That's pretty much all the questions I have. But I'm wondering if there's any, you know, any other stories you would like to tell us? Any other pieces of your work you'd like to highlight in this area of systems practice?

Josh:I'll just say that I think there are some really exciting communities of practice that are making a lot of headway now. So more a forward looking comment. So there's, you know, for example, the planetary health is an increasingly powerful frame that brings together, how the health of natural systems is linked to human health. And I think getting a lot of traction around understanding climate change and how that there really is an urgent issue, and arguably one of the, you know, the biggest, if not the biggest global health challenge for the 21st century and the massive burden of pollution that comes from, you know, our, you know, people two out of three people around the world not having sanitation and wastewater not being treated effectively and all kinds of pollution that goes into water, soil, air, you know, and chemicals that are in them. And so these are, I guess what really gives me hope is that, for this system's movement to really make a difference we need people who are in policy making positions, in making financing decisions, in governments and private sector and NGOs and so on, to be empowered to act and to see these solutions being more effective. And so I think we're at a point where I wouldn't say it's necessarily a tipping point or inevitable, but it really seems like there's growing momentum and certainly around the sustainable development goals from the United Nations as really powerful integrated frame. And so to me it's really incredible that the world has committed to 17 goals in a really integrated way, an indivisible set of goals to achieve any one of them to, you know, to end hunger is connected to all of the improvements in health, all the improvements on bio diversity and so on. And that's a really powerful frame that we can act on now. And we better seize the opportunity, you know, to do this and to do it smart. So for me, you know, tons of work to do, but a lot of excitement ahead.

Sam:Wonderful I love it when people end on a note of hope.

Josh:Yeah. I've been criticized as having rose colored glasses more than once, but it's way more fun to be in the world.

Sam:Yeah, exactly. I think when you take the systems view of life, it's sometimes very hard to, to always invoke that sense of hope given some of the complexities that we face, but it's wonderful to hear that coming through your work. Thank you for that. If people wanted to get in touch at all, is there a best way to do that? To learn more about your work or to ask specific questions?

Josh:First step is to visit our website, which is bridgecollaborativeglobal.org, and I'd be happy for folks to reach out to me personally as well, so if you want to share my contact information.

Sam:Okay, great. Thanks so much Josh. It's been lovely to speak to you and to hear about your work, it really does sound like some pioneering work and some really, really important work that you're doing as well. So thank you for that. Thank you for your time.

Josh:Yeah, super. Thanks so much, Sam. I appreciate it.